Ellen Zweig: Fiction Of The Physical

Navel-Gazers #50 is an interview with Ellen Zweig who is going to talk to us about Fiction Of The Physical. This collection of experimental spoken word from the 1970s/80s era caught me completely off-guard when I was poking around on the always-intriguing Phantom Limb label. What strikes me immediately about these pieces is their clarity: the clarity of the voices, the arrangements, the textures - and, throughout it all - an indelible clarity of purpose on the part of the artist which is really unlike anything I’ve ever encountered. Perusing the liner notes, the plot thickens: apparently we’re hearing a technique which Ellen calls the “human loop”, where performers repeat a phrase over and over onto tape, culminating in a collage of voice-loops which veers off into a life of its own. As for the instrumentation, it's described using terms such as “fourth world” and “fourth wall” - all I know is by the fourth track it’s as though I’m submerged in some sort of underwater gamelan. I’ve never heard of Ellen Zweig before this… or have I? She’s better known for her work in writing and video installations than for music - she seems like quite a busy person in general so I’m pleasantly surprised she has time to talk to us! Let’s hear what Ellen has to say.

AC: Thanks for joining me on Navel-Gazers! Why don’t you first tell us about yourself and your early background as an artist leading up to the time these pieces were developed?

Ellen Zweig: I started as a poet, and like many poets of my generation, I wanted the poem to be oral. I was interested in the rhythms of ordinary spoken American English. English is a language in which stress is phonemic (stress gives us meaning; different from a language such as Chinese in which tone gives meaning). From the beginning of my career, as a writer, performing poetry out loud was to compose and perform spoken language as music.

In the 1970s, performance became a new and exciting genre. Accepted in the visual arts world for my language performances, I began to use slides (with slide dissolve machines) and Super 8 film, sometimes even props, to stage my performances. In other words, my performances became visual as well as aural. At the same time, I was working with tape and often performed in the context of the experimental music world (text-sound composition, sound poetry - there were many festivals, especially in Europe).

I loved this time of crossing genres, crossing worlds.

AC: I suppose you must have crossed paths with all different kinds of artists. Are there any whom you particularly remember or who made a strong impression on you?

Ellen Zweig: In the 70s and early 80s, when I had become a performance artist, I was influenced first by Eleanor Antin, especially her King of Solano Beach performances. For my very first performance, I dressed as a crow, went out on the streets of Ann Arbor, Michigan and told people: “I’m just a common crow and I have errands and expectations.” I was also welcomed by Rachel Rosenthal at her espace dbd in Los Angeles where I was invited to perform a more theatrical piece, “Fear of Dining and Dining Conversation."

In the music world, I was very much influenced by minimalist composers such as Terry Riley, Steve Reich, Philip Glass and Harold Budd. In my writing, I mirrored their methods by repeating phrases with slight variations. This is when I developed the “human loop” that you mentioned in your introduction.

And through it all, there was Armand Schwerner, poet, performer and dear friend. We did two collaborative performances, “Everything You’re Giving Me Is Just Things You’re Giving Me” and “Teratophany.”

AC: Let's talk about that human loop. Could you explain exactly how it works?

Ellen Zweig: In the early 80s, I was making work at Harvestworks in NYC. In those days, it was almost totally run by women, and it was affordable, priced for artists. We were working with tape (actual tape on reels!), cutting and splicing - digital has made all of this so easy you barely notice it. I worked with two incredible engineers, Connie Kieltyka and Brenda Hutchinson. I was making pieces with multiple voices and I remember talking to Connie about looping certain phrases as a bed of sound over which we could mix my voice. But I didn’t like the mechanical repetitions of a phrase when it was looped. Steve Reich had done some innovative pieces, “It’s Gonna Rain” and “Come Out” but I didn’t want to copy his technique of repetition and decay.

As an experiment, I recorded several voices, saying the same phrase over and over for a minute. Next I had to decide whether to start all the voices at the same time or start them one by one like a fugue. I tried both methods. The different speeds of the voices would cause them to chorus and separate. If they all started at the same time, they would go out of sync and sometimes back in. If they started one by one, they would come into sync unexpectedly, often on an important word or phrase.

AC: This explains the “chorus” sound of the voices. How remarkable that you arrived at that effect organically by such an unusual approach!

There are five pieces on ‘Fiction Of The Physical’: four and one bonus track. In what order were they conceived?

Ellen Zweig: The order was-

Green Silk 1978

Network of Letters 1980

Sensitive Bones 1980

The Act of Watching 1985

If Archimedes 1991

Green Silk and Network of Letters were part of a series I worked on in the 1970s, early 80s, which I called “Anti-Buddhist Expectation Love Line.” Buddhism teaches that desire and expectation cause suffering. Instead of doing away with desire, I decided to go for it…as much expectation and desire as possible…where would it lead?

Sensitive Bones was an homage to one of my childhood passions, Marie Curie.

The Act of Watching was the last section of a series called “Impressions of Africa: Variations for Raymond Roussel.” In this series, I explored fantasies of Africa, the biases of traveling Westerners, and the stance of an outsider yearning to be inside…

If Archimedes was part of a collaborative installation called Critical Mass (with Meridel Rubenstein), that circled around a woman named Edith Warner, who lived near Los Alamos at the time of the making of the first atom bomb.

Perhaps you can see from these explanations, that I like to work in series or on projects, exploring a subject in many different ways.

AC: Let's talk more about what we're hearing... the one voice heard on all the pieces, I assume is yours. I then hear other voices on 'Network Of Letters' and 'If Archimedes', who are they?

What can you tell us about the instrumental arrangements? When I cross-reference them with your chronology above, it seems they got more ambitious - and percussive! - over the years.

Ellen Zweig: Yes, I’m on all the pieces…that’s my voice.

For ‘Network of Letters,’ I wanted a male voice as a contrast to mine and also because of the content - rejected love letters. The male voice is Glenn Davis, a poet I knew back then.

For ‘If Archimedes,’ I asked Joan La Barbara (the great performer and composer) to do some improvising on the sounds of the words. She also read some of the text. Also reading is the poet Nathaniel Tarn. David Dunn, the composer, and I played the sculptures of Tony Price. All of these people were then living in Santa Fe, New Mexico, where I was producing this and other sections of the work Critical Mass.

The story of the music is something that I can begin but you’d have to ask the two composers to answer your question in more detail. ‘Sensitive Bones’ and ‘The Act of Watching’ were originally collaborations with a composer named Gregory Jones. I had been out of touch with him for many years. When I tried to get his permission to use his music, I discovered that he had passed away and his estate refused permission. Unfortunately or perhaps fortunately, I didn’t have the separate tracks for these pieces, only a mixed version (remember these were made on tape). I asked the sound designer, Quentin Chiappetta, (who does the mixes for my videos) if he could erase the music. And he could! It was a long shot, but wow, technology and genius sound designers, just wow.

With files containing only my voice, I asked David Weinstein to compose music. Later Dylan Henner composed the music for ‘Green Silk,’ ‘Network of Letters,’ and added music to ‘If Archimedes.’ I was, of course, involved in these collaborations, listening to drafts and making suggestions, but I chose the composers because of the music that they made, so I trusted them to do justice to my performance and my words.

AC: I like the long lifecycle of these pieces, it’s as though they are continually being invented!

‘If Archimedes’ is a favourite of mine… I wonder if you could tell us more about the Critical Mass project and the sources of the text? That sounds intriguing.

Ellen Zweig: “Critical Mass” was a seven year project, completed in 1993, a collaboration with Meridel Rubenstein, with technical advice from Woody and Steina Vasulka. In Critical Mass, we brought photography, video, and text together to examine the forces of domesticity and history that led to the creation of the first atomic bomb. We took as our subject the life of Edith Warner, a friend of J. Robert Oppenheimer, who lived near Los Alamos. She had dinners for the scientists and was close to the people of the Pueblos. Her house was a meeting place.

The installation, “Critical Mass” premiered at New Mexico Museum of Fine Art in Santa Fe. It later traveled to List Center for the Visual Arts (Massachusetts Institute of Technology, Boston), Scottsdale Center For the Arts (Arizona), Museum of Contemporary Photography (Chicago), etc.

‘If Archimedes’ was the text/sound composition for “Archimedes' Chamber,” one of the major parts of the installation. Approaching “Archimedes’ Chamber,” you first saw two columns of photographs on either side of a column of four video monitors. On the monitors were images of Edith’s house and the landscape of New Mexico. These images moved up and down the four monitors behind images of burning. (this was analogue video, by the way, so the mix of images was achieved with a Hearn video mixer. One day I asked Steina why it was called a “Hearn” and she said - “oh, it’s because Bill Hearn made it.”)

One day, Woody Vasulka had a great idea. Why not take the photographic slides we had of the New Mexico landscape, put them in a vice-like contraption, add a video camera facing the slides, then use a small blow torch to burn holes in the slides…we all threw ourselves into this activity. The result looked the way it used to look when film got caught in the gate of a projector and began to burn. Beautiful burning, but also an apt metaphor for our subject matter.

Ok, back outside “Archimedes’ Chamber,” watching this burning…You could hear ‘If Archimedes,’ from outside, but better if you entered the Chamber by walking around the column of monitors. On the floor of the Chamber was a round screen with images of burning. These were projected, not by a conventional video projector, but by a device I made with a small monitor and a first surface mirror in order to make the reference to Archimedes’ burning mirrors clear in the actual physical installation.

I wrote the text of ‘If Archimedes’ after doing a lot of research and reading. I noticed that Oppenheimer was often vilified. I also discovered that Archimedes had created weapons to save his city of Syracuse from invaders. One of the weapons was described as “a great burning mirror” that used the sun to attack ships approaching the harbor. I thought - if Archimedes created this weapon and was considered a hero for saving his city, then Oppenheimer was a hero too, but if Oppenheimer was a villain for creating the atomic bomb, then Archimedes was a villain too…I couldn't answer this question…it was an “if” situation…

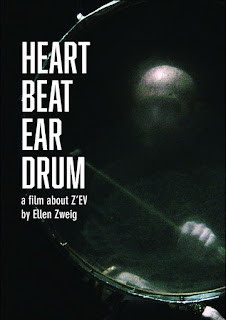

AC: When you mentioned earlier playing the sculptures of Tony Price, you reminded me of another thing I wanted to ask you, which is nothing to do with ‘Fiction Of The Physical’ but would be of interest to our readers. Apparently you directed the documentary Heart Beat Ear Drum about the musician Z’EV? Please tell us the story behind that. I saw the film a few years ago, and it made a strong impression on me.

Ellen Zweig: In my video work, I use documentary methods but I don’t really make docs. Z’EV was a close friend and I’ve always loved and supported his work.

I thought at the time that it would be fun to interview him and follow him around to concerts. I had no idea how many years it would take to make Heart Beat Ear Drum. The filming, as I predicted, was really interesting and fun. I met many people who had collaborated with Z and others, childhood friends, critics…we filmed in London, New York, Holland...

Z provided me with some archival materials - old films and videos - but I had to get permission to use clips from these materials. This took almost a year. I had to research who had filmed the performance, who held copyright, who could give me permission (hopefully for free or for a nominal fee). I wrote grants for the film.

Another part I really liked was editing, but I reached a moment when I had an edit and I knew it wasn’t there yet. I hired Lili Chin to have a go at it. She immediately pointed out that all the interviews were of people Z’s age or older. Out I went with my camera to interview the younger ones who knew Z mostly from recordings.

Finally, I had a film…I suppose the biggest surprise to me was that the film is about, most deeply, something close to my heart. Here was an artist who lived his life as art; his music, his sculptures, his living environment - it was all an example of a person who didn’t separate his life and his art.

The premiere of the film actually happened in China in 2013. I was an artist-in-residence at the Swatch Art Peace Hotel in Shanghai. I hired Zhang Hangya to subtitle the film in Chinese and it screened at the Fei Art Center. I subsequently re-edited the film and premiered it in Paris in 2015 at L’Etrange Festival.

AC: Yeah I saw it at Cafe Oto, which was packed out for the screening!

To return to ‘Fiction Of The Physical’, I was wondering how you got an idea to finally put this material out into the world in 2023, and how it ended up on Phantom Limb, on vinyl, with the new artwork/ liner notes etc?

Ellen Zweig: That’s a simple question to answer. James Vella of Phantom Limb contacted me about Sensitive Bones and The Act of Watching. I’ve already told you the story of how Quentin Chiappetta made it possible to use those files. As David Weinstein and I were working on those, Dylan Henner asked me if there were other pieces that he might play with…I sent If Archimedes, Network of Letters and Green Silk…

When we were ready for a cover and liner notes, etc., I sent images that were used in the performance of Sensitive Bones (photograms I made with Alice Prussin) and photos of me performing. I’m very happy with the design that came from Phantom Limb…Vella wrote the liner notes (with input from me).

Ellen Zweig: Right now, I’m deep into editing the many parts of a large project about concepts of “hometown” in China and America. The Confucian concept of ‘hometown’ is the place where your Father’s ancestors are buried. I was curious to see how many people still thought this way. And curious to know if Americans also had a consistent concept of hometown.

The project seemed stalled because of the pandemic, but in a moment of desperation, I realized that I could do interviews of Americans remotely as long as the people I was interviewing could film themselves. In China, the lockdowns hadn’t happened yet, so my assistant, Zhang Hangya, was able to film the interviews in person.

The project centers around a discussion I witnessed in a park in Shanghai in 2014 about a song, “Clouds of My Hometown.” This song, originally written by a Taiwanese songwriter, was made famous at the 1987 New Year’s Gala CCTV show, sung by Fei Xiang. It’s a sentimental song about yearning for home. Fei Xiang is complicated - half American, half Chinese - he grew up in Taiwan. Singing at the Gala got him in trouble with the Taiwanese government, so he continued his career in the PRC, but his performances were often a bit too sexy for the Chinese government. After 1989, Fei Xiang moved to New York where he became a star in Broadway musicals. This man, with his complex identity, introduces his song by mentioning a hometown in rural China, the hometown of his Mother’s family. And many years later, a group in Zhongshan Park discuss the lyrics.

The project is still evolving… fragments. An installation, a website, a feature length video…

AC: I’ve previously interviewed at least one other artist (Enzo Minarelli) whose work somewhat reminds me of yours, but ‘Fiction Of The Physical’ is really unusual. Do you ever come across music where you think: that’s similar to what I was doing?

Ellen Zweig: No - it just never happened that way. In the late 70s and early 80s, I lived in the worlds of poetry, performance, new music…there were influences such as the minimalist composers, but I felt I was forging my own path. In fact, it was compelling to do something different, often against what others were doing. The composers I worked with then, Gregory Jones and John Di Stefano, made music that I thought would work with my language compositions. I suppose there was a kind of recognition in that.

AC: Generally, what music do you like? We’ve mentioned names here like Steve Reich, Joan La Barbara, Z’EV… what other music interests you? I wouldn’t normally ask such an unimaginative question here - I suppose since you’re not primarily a musician, I’m more curious about this!

Ellen Zweig: My musical tastes have always been eclectic. I love Guillaume de Machaut (and other non-religious Renaissance music), Mitsuko Ushida playing Schubert, Yo Yo Ma and Meredith Monk, Carl Stone and 1930s Shanghai popular songs. Brave Combo (a Texas band that plays rock and roll polka!), Cornershop, Robert Wyatt. You see what I mean, eclectic.

My early musical taste was jazz, but not the jazz that’s popular these days…I love John Coltrane and many of the musicians who played with him. In the late 60s in NYC, we used to go to Slugs, a small jazz club. It was the kind of place where you could sit at a table up front, close to the stage, and the musicians would come down during a break and say hi. Every Monday, Sun Ra and his Arkestra played there for free (he was pretty much unknown at this time).

But the most memorable time I had at Slugs was the evening that Rashid Ali couldn’t stop playing…here’s what happened. Pharaoh Sanders, Leon Thomas, McCoy Tyner, Rashid Ali - an incredible group of musicians. As is customary with this kind of performance, each person got a chance at a solo…when Rashid Ali started playing, the others went out back for a smoke…Ali was in a groove on the drums, and when the others came back on stage, he didn’t stop, didn’t even notice them…they went out back again. I suppose he played for at least a half hour. Finally, the others got on stage, looked at him, looked at each other, and blasted music. Ali was startled, looked like he woke out of a trance, went out back. It was the most phenomenal drum solo I’ve ever heard.

AC: Wow you were lucky to see that! What a great quartet, all of them no longer with us.

Has the 'Fiction Of The Physical' release revived any of your interest in making this kind of work, or are you turning the page and leaving it in the past?

Ellen Zweig: I never completely left the work of ‘Fiction of the Physical’ although the connection with my video work might not seem obvious. I’m still interested in the rhythms of language and I view poetry as a time-based medium. In my videos and video installations, I combine language, performance, and documentary images.

AC: I’m glad to hear that! And I’ll be following along to see what you’re up to next.

Thanks for talking to me.

Ellen can be found at her website https://ezweig.com/.

Images

0) 'Fiction Of The Physical' cover image (Alice Prussin)

1) 'Sensitive Bones' performance

2) 'Crow' performance

3) 'Green Silk' set

4) 'Sensitive Bones' performance

5) Archimedes Chamber from 'Critical Mass'

6) Archimedes Chamber from 'Critical Mass'

7) 'Heart Beat Ear Drum' DVD cover image

8) 'Hometown Project' images

9) 'Act Of Watching' image (credit: Michael Shay)

10) 'Green Silk' performance

.jpg)