Thomas Dimuzio: Headlock

Navel-Gazers #29 is an interview with Thomas Dimuzio who is going to talk to us about Headlock. Mr Dimuzio is an artist whose name is synonymous to me with secret underground music and the outer limits of sound. This album, released on the Generations Unlimited label in the waning hours of the 1980s, is his earliest - at least as far as I’ve ever been able to tell, maybe we’ll learn otherwise? - and it’s a work which has loomed large in my thoughts ever since learning about it at an independent record store in Philadelphia where I was working in the early 2000s. What I love about ‘Headlock’ is that while it’s dark and ambient and it’s got all the murky, grim atmosphere of that sort of music, it’s never - even remotely - monotonous or repetitious.. the palette of sounds and the complexity of the soundscape are just staggering. These days I’m having fun reading through the list of sample sources provided on Bandcamp for ‘Headlock’ - it ranges from instruments like clarinets and guitars, to found sounds such as duct tape and washing machines, to what I suppose are mystery listings: ‘’Banoodle’, ‘Davlarv’s Car’, ‘Patronized Humoplasms’ among an assortment of others left to the imagination. Let’s unravel the mystery with Thomas Dimuzio… or, will we just plunge deeper?

Navel-Gazers #29 is an interview with Thomas Dimuzio who is going to talk to us about Headlock. Mr Dimuzio is an artist whose name is synonymous to me with secret underground music and the outer limits of sound. This album, released on the Generations Unlimited label in the waning hours of the 1980s, is his earliest - at least as far as I’ve ever been able to tell, maybe we’ll learn otherwise? - and it’s a work which has loomed large in my thoughts ever since learning about it at an independent record store in Philadelphia where I was working in the early 2000s. What I love about ‘Headlock’ is that while it’s dark and ambient and it’s got all the murky, grim atmosphere of that sort of music, it’s never - even remotely - monotonous or repetitious.. the palette of sounds and the complexity of the soundscape are just staggering. These days I’m having fun reading through the list of sample sources provided on Bandcamp for ‘Headlock’ - it ranges from instruments like clarinets and guitars, to found sounds such as duct tape and washing machines, to what I suppose are mystery listings: ‘’Banoodle’, ‘Davlarv’s Car’, ‘Patronized Humoplasms’ among an assortment of others left to the imagination. Let’s unravel the mystery with Thomas Dimuzio… or, will we just plunge deeper?AC: Thanks for joining me here! So… it’s actually the perfect place to start: was ‘Headlock’ your earliest work? And why don’t you tell us more generally who you are, where you’re from and how you got started as an artist originally.

Thomas Dimuzio: It's great to be here, Andrew, and thank you for such a lovely introduction. Headlock was actually my second release; the first was Delineation Of Perspective, which was also on Generations Unlimited.

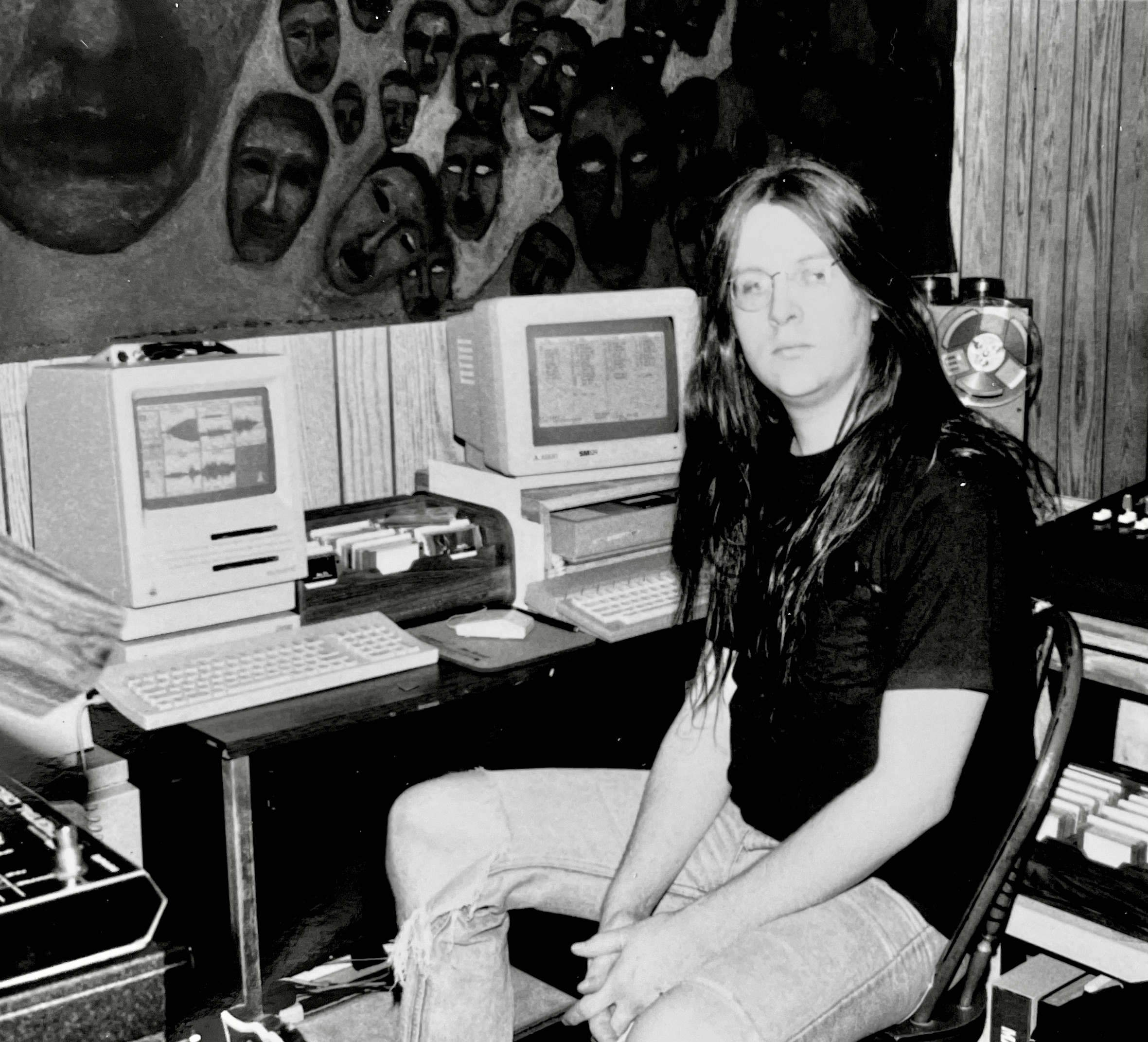

There’s a bit of a backstory to Headlock which begins with my first GU release, but I’ll start with a bit of my background. I’m originally from the south hills of Pittsburgh and became immersed in music and sonic abstractions while in high school. Over the course of a few years my friends and I had produced hundreds of original recordings — experimental music, prog rock, improv, and even comedy. Later I went to music school in Boston but only for a couple semesters as I quickly decided to leave school but stay in Boston to concentrate on music. Boston was a great city for rock and jazz if you were in a band, but the music I made wasn't embraced at the time (I’m not even sure that it is now) and I was also working in a bubble being largely ignorant of cassette culture and the DIY music happening on the far fringes back then. My girlfriend, who’s now my lovely wife (aka Banoodle), used to work on paintings in the evenings while listening to WZBC Boston College radio. These adventurous late night shows were off the beaten path and it didn’t take long for me to contact the station, as I thought my music would fit into their format. One of the DJs there said I should send my tape to Dave Prescott, who hosted a weekly radio show. Within a week Dave wrote back and kindly offered to release my tape on his label, GU. We started hanging out and Dave soon encouraged me to release an LP of new work, which eventually became ‘Headlock’.

AC: Just checking out ‘Delineation Of Perspective’, that looks like two long tracks whereas ‘Headlock’ consists of ten shorter tracks. It’s got me thinking about all the decisions along the way, coming up with structure, titles etc… what was the process for ‘Headlock’? What came first and how did things develop?

Thomas Dimuzio: ‘Delineation of Perspective’ was originally a cassette release with 6 tracks, but maybe you heard a version that digitized each side as a single piece. All of the tracks on ‘Delineation of Perspective’ and ‘Headlock’ stem from improvisations and were later built upon as compositions. The structures emanate from the improvs, but of course all bets are off when composing as anything can happen, but for the most part the form or linearity of those original ideas remains intact. Some pieces like Wake Up From That Dream Young One… were comprised from many improvs and ideas, and as it began to take shape, then specific ideas came to mind, like the guitar section near the end.

Ultimately I tend to sit back and let these improvs tell me where to go next. I may hear an idea or sound while listening back and then try to reinforce those sounds and textures. The titles almost always come last and are a result of listening back to the final piece or album, and are often in relation to the other titles on the record. Titles are how I try to unify an entire work after the fact.

AC: Interesting approach to composition! So what were the original improvisations? would that have been on any particular instrument or device, or is it a live layer of the samples? Do you still use this method of building around an improvisation?

Thomas Dimuzio: Most were done playing a sampler onto tape as this was the dawn before the digital audio revolution. Pre-production was key as I had to capture and loop the samples before I could improvise with them, but that was all part of the process.

Certain tracks used more adventurous approaches: Inherent Power and the Space Between played a bicycle turned upside-down with cards flapping in the the wheels; Settlement was based on pushing a metal shopping cart around outdoors on a cement sidewalk; Sallow sampled the ‘singing' pipes from my kitchen sink, and Moneytable at the Countinghouse randomly triggered a hodge-podge of disparate non-musical samples. Although improvisation spawned many of these ideas, the processes applied after the fact were unique to each piece and could take it any direction. In many respects improvising on a sampler was akin to (real-time) editing on a DAW—especially if multi-samples were cut up and arranged across the keyboard. An orchestra of sound, like Cage's prepared piano, but entirely digital.

I love improvisation and to this day continue to spawn many of my studio-based compositions this way.

AC: I love all those organic sounds, and it’s great to learn about the pipes on ’Sallow’, my favourite track here.

Thomas Dimuzio: Thank you, it’s amazing how orchestral those few samples turned out to be.

AC: Referenced in our introduction, there are some wacky credits on the sound sample list for ‘Headlock’. You’ve explained who “Banoodle” is and about the bicycle, the kitchen pipes… let’s dig deeper. Who or what are Po-Po, the Sullivans? Tell us about the junkyard, woodshop, the washing machine, etc… anything from the list which might be of anecdotal interest!

Thomas Dimuzio: Back in the day I was on a mission to sample just about anything; some of those credits are literal descriptions while others are more obscure.

Right off, many samples were vocalizations of my friends: Kish, Jim Reed, Banoodle, and Babs. My old band was called Patronized Humoplasms and were sampled liberally on ‘Wake Up From That Dream Young One’; Po-Po was our dog and I'd modulate her vocalizations by gently squeezing her sides. The Sullivan’s were our reluctant neighbors and a family of four who’d scream daily at their fully grown kids; things like, "Dennis!! Get up it’s 9:30!!" Our poor housemate Warren Boes’ bedroom window was 2 feet from their kitchen window so he was privy to all of this and awoken so many mornings that, out of sheer frustration, just embraced it and placed a mic hidden in a sock on his windowsill; only to hit the record button each morning like a snooze alarm. Years later Roger Miller and I both realized that we were each one time neighbors of the Sullivans. Mission of Burma once lived in the house on their other side! So the washing machine is a plain old washing machine, and the woodshop was the wood shop at the Museum School of the Fine Arts in Boston — the joiners, planers, bandsaws and other machines in there sounded beautiful. The junkyard was right behind our house in Newton, Massachusetts and was essentially a superfund site. We grew tomatoes in our garden but they tasted like motor oil — just add vinegar! Nearly every morning at 7am the junkyard would start up their backhoe to start smashing cars. It was crazy!! So much noise, but after a time it was the quietness on the days they weren't working that used to wake me out of my sleep. Such an incredible source for industrial samples and with lots of Bostonian banter thrown in between, and it was all right there in my backyard! Bear in mind that this junkyard was contained to a single lot in a residential neighborhood, and the last time I visited I was shocked to see the junkyard gone and with a new house built atop that chemical dump.

AC: Haha Thomas these stories will go down in Navel-Gazers history! I’m compelled to go back and listen again…

Cool to see the Boston connection with Roger Miller from Mission of Burma. On your website I can see that you’ve worked with everyone from Fred Frith to Matmos to GG Allin to KK Null. How did you get involved with all these different artists over the years? Any special recollections?

Thomas Dimuzio: While working on Headlock I had not yet performed as a solo artist. My first solo show was in early 1990 at Generator in NYC a few months after Headlock was released, but it wasn’t until after moving to San Francisco in 1996 that I started to perform regularly. The Bay Area music scene has always been a hub and shows were aplenty, so there were many opportunities to play with others; especially when sharing the same bill. One of my favorite tactics was to crossfade live between acts, and this often led to playing full-length sets together outright. Many long-standing collaborations spawned out of these initial encounters, especially early on with regards to locals like Wobbly, Matmos, and Scot Jenerik.

Chris Cutler and I first played together in 1994 in a trio with Charles O’Meara (aka C.W. Vrtacek) in Hartford, CT. Five years later Chris and I rekindled as a duo which led to playing in a trio with Fred Frith. Our performances are well-documented on Golden State, Dust, Quake and Preacher in Naked Chase Guilty. Joseph Hammer, Dan Burke, Due Process, Voice of Eye, Alan Courtis and 5uus are all artists I’ve worked with over the course of many years, and all of these relationships started after playing together live or meeting at shows.

I’m an improvisor at heart and playing with others in this realm is music at its most elemental and visceral form, and this often leads to pure magic.

As a mastering engineer I’ve worked with hundreds of artists including GG Allin, KK Null, clipping., Nels Cline, Negativland, ISIS, Yuka Honda, Firesign Theatre, Psychic TV3, AMM, Jonathan Snipes and the list goes on. Of course much of this work is performed without the artist present, but not always!

AC: I like the application of a recording technique (crossfading) to performance.

Thomas Dimuzio: That’s kind of been a life’s mission for me: playing the recording studio like a musical instrument and bringing those processes to the stage, whether analog or digital.

Thomas Dimuzio: I was messing around with some newly recorded samples when something went perfectly wrong — there was this beautiful phasing sound happening that I hadn’t heard before so I decided I’d better record it before it went away, and from there the piece began. Just to get the technical details out of the way, I was recording to a Tascam 388 1/4” 8 track tape with timecode feeding an Atari ST running Dr. T’s KCS MIDI sequencer which in turn triggered two Roland S-50 digital sampling keyboards and a Yamaha TX81Z FM synthesizer. MIDI-controlled effects also factored in heavily via the Lexicon PCM70, LXP1 and LXP5. Real-time MIDI and computer control of effects parameters helped to animate the otherwise static and unchanging nature of a digital sample, and modulating parameters such as reverb time, delays, pitch shift, panning, and filters helped to stereo-ize the sampler’s mono output.

The overdubbed drums on those drones were comprised of rhythmic loops of varying lengths all freewheeling against the others via Dr. T’s Keyboard Controlled Sequencer. True to its name, KCS could trigger and record multiple sequences simultaneously via the computer keyboard which allowed it to function more like a loop-based musical instrument. A short fanfare-style intro was then built from samples and voice to lead into the drones. So with the intro and first part complete I decided to add a bunch of disparate parts with the intent to meld everything into a single piece. Each part was built sequentially due to the linearity of tape, so out of the drones stemmed a bridge forged out of unsourced operatic shortwave samples, and this led to a new section based on repetitive structures, again mostly from samples, but pitch and consonance were not a consideration; Banoodle is in this section. A tolling bell transitions into the jarring and heavily processed Patronized Humoplasms samples which were all run through a spectral inverter and alternated back and forth between the left and right channels.

These DAW-like edits and processes are taken for granted today, but this section was stitched together using processed samples via MIDI. More unsourced shortwave samples are collected for the next section, but this time with the message “very good; very attentive” rolling back and forth as it morphs into “as they sit watching their TVs”, and all underscored by a secondary drone that slowly modulates via MIDI pitch bend to the harmonic fundamental of the next section. There I played 12-string acoustic and 6-string electric guitars for a kind of melancholy progression. The acoustic guitar was double-tracked, but the second track was mistakenly a quarter note off and left in as a happy accident. The odd percussive and vocal samples were recorded in 1986, before I even owned a sampler, from my apartment window at the corner of Hemenway and Haviland streets in Boston. A coda comprises an unresolved loop playing forwards and backwards and wraps up the LP, but on the CD reissue I added the crackling vinyl and the sound of the needle picking up from the original Headlock LP. Yes, revisionist history: on the record; for the record.

This all reminds me how the record had to be mixed. Most of the tracks on Headlock crossfade into the next, and the only way I could pull that off at the time was to use three 2 track decks for the mix: two digital, and one analog. Each track was mixed to a Toshiba-DX-900 VHS deck that had 14-bit PCM digital encoding. This was before DAT machines were allowed to be imported into the US from Japan, and this early version of a digital recorder was the only way to avoid tape hiss on the second generation analog mix that ultimately became the master. I borrowed another Toshiba deck from a friend and used the two machines to crossfade the mixes to 1/4” analog two track. There was no undo and those mixes became each side of Headlock. This process seems crazy by today’s standards but was the only way for me to realize such music at the time.

AC: What a wonderful description of the recording process, in all its pre-1990s complexity.

Before we start to wrap up here I just wanted to ask about the album cover. What's the story with that? Any reference to those kitchen pipes?

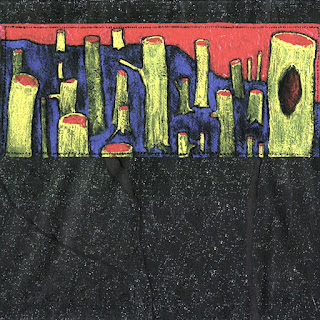

Thomas Dimuzio: The cover art is based on an original painting by Anne Bonham (aka Banoodle) made with acrylics on tar paper. Her imagery was perfect for the new record as she was working on that and similar paintings all the while as I was recording, so it surely influenced the vibe, and vice versa. The cover of Sonicism also highlights details from another tar paper painting of Anne’s from this same period. Her tar paintings all varied in length and one stood 20 feet tall. I had trouble distilling the image down to a photo so Anne lovingly made a miniature version on a little piece of tar paper which I glued to a dot-matrix printed texture and matted against black cardboard for the cover.

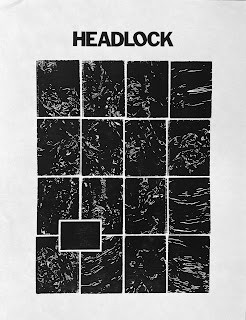

The primary image on the back cover I created in MacPaint and also snapped the black and white photos framing the image, and even doodled the little Headlock mascot. Adhesive vinyl lettering was used for the title — talk about cut and paste. There was a laser printer where I worked that I used to make inserts that shipped with the original LPs. I thought the laser-printed text looked so slick at the time, which is maybe why I went a little overboard with the liner notes. The image on the other side of the insert was made from photocopying garbage bags, and again at the office; if they only knew. "Not responsible for systems damage."

AC: Maybe we can include the back cover and/or insert images in our published interview, so people who don't have the physical album can check those out!

I'd like to thank you very much for talking to me. It's been great to get the scoop on Headlock. Are you working on anything currently you'd like our readers to be aware of?

Thomas Dimuzio: It’s been my pleasure, Andrew. Thank you for your enthusiasm and for taking me back to those early sessions. I can’t believe it’s been 33 years!! Pro Tools soon came along and I eventually left analog tape and many of those arcane processes in the dust, so it was a trip digging back into such ancient techniques.

The last few years have been ultra-productive for me and with many new releases hitting the streets. 2020 brought Sutro Transmissions (Resipiscent Records, LP) as my first proper Buchla record; Slew Tew (Gench, CD) as a compilation of compilation tracks playing more like an album rather than a bunch of unrelated tracks, and Balance (Gench, CDx3) which showcases 28 live shows in collaboration with 48 different artists in duo, trio and combo formations. 2021 saw LCM (Erototox Decodings, LP) documenting my early Buchla performances at LCM in Oakland; Losing Circles (Yew Recordings, LP) featuring, you guessed it, more Buchla and in duo form with Marcia Bassett; Redwoods Interpretive (Oscarson, LP) with Wobbly and Alan Courtis where we did a studio session and played 3 shows in the span of Alan's 48 hour visit to San Francisco; Dimmer dreamt up midRem (Deathbomb Arc, CD), a sleep-induced opus that made it to some best of '21 lists; and the first of my Sculpting Electric series, In The Ice Phase (Gench, download) featuring live in-studio modular synthesis compositions.

Works in the can include the debut of Readybox, a live musique concrete/ electro-acoustic duo with saxophonist Phillip Greenlief; Cracking the Surface, a quartet entrenched in all things Skatch™, with Tom Nunn, David Michalak and Scott Looney — both records were recorded at the now defunct Fantasy Studios in Berkeley.

New works in progress include a recording project with Voice Of Eye and Tuvan throat singing maestro, Soriah. Dimmer is working on a new record plus a Cinechamber piece for 18 speakers and 10 screens for Naut Humon's Recombinant Media Labs Festival for fall 2022. Last September I opened for Negativland on their west coast tour and, considering the pandemic, all went remarkably well, so I'm hoping that 2022 will ultimately bring live music back to the stage; especially for artists like me who are happy to play to smaller audiences.

AC: Here’s hoping! Thank you again!

Thomas can be found at his website http://www.thomasdimuzio.com/ and at Bandcamp.