Mnemonists: Gyromancy

Navel-Gazers #46 is an interview with William Sharp and Mark Derbyshire of Mnemonists who are going to talk to us about Gyromancy. Produced in Colorado in 1983, this is one of the most unusual recordings I’ve ever heard: a 40-minute, 40-year-old, towering, imposing accumulation of musique concrète which unfolds to this day like a living sculpture of sound before ones ears. I’ve always thought of the Mnemonists’ work - along with that of Mnemonists’ more prolific musical cousin Biota - as something like its very own species of sound… and there’s an explanation for that. These productions, culminating in ‘Gyromancy’, were ones which evolved organically from the use of radical and complex recording and processing techniques - ones virtually unheard of at the time of their release, and in fact perhaps even less familiar to us denizens of today’s more homogenised technological universe. I’ve been in contact with Mr. Sharp for the past 24 months and I sense a real determination to do ‘Gyromancy’ justice in this discussion. That’s probably why he’s suggested that we also track down Mark who was - crucially - the studio engineer on this most curiously engineered album. Let’s decipher ‘Gyromancy’ with Mnemonists…

AC: Thanks for joining me on Navel-Gazers! Firstly why don’t you tell us about yourselves. What were your respective backgrounds? What was your level of interest in music vs. art generally vs. technology vs. radio broadcasting vs. whatever else? And how did you meet each other?

William Sharp: Mark and I were both involved with college radio at the time. I had been active as a producer for programs at KCSU (Colorado State University) that featured US, British, and European experimentation, primarily in rock and jazz. I was still in school, working toward a Bachelor in Zoology, my mindset split between the arts and sciences. In 1979, I promoted a stop for the Gong Manifestival in Fort Collins. In bringing Mnemonists together that same year, my thinking was conceptual: instrumental sound meets spoken word and then balancing with visual art. There was a reasonable amount of independent label activity on the 1970's US scene, and there were printing and pressing plants willing to do small runs. Mnemonists envisioned multi-media packages and the pathway was there.

Mark Derbyshire: While I don’t believe they intended this, my background was largely defined by my parents. Both grew up in the Great Depression, and in particular my mother’s parents wanted her to be independent. She first pursued a career as a concert pianist and in the early 1940s was a substitute anchor for a national television network. Later she became a paralegal in modern vernacular, and in the 1960s settled into computer science.

My father studied to be an electrical engineer and ultimately became a professor of theoretical physics. I dallied in just about everything they did.

Growing up in an academic family in the 1960s in Fort Collins, I was fascinated with mathematics, science, and music. I took classical piano lessons from my mother before switching to cello, which I had wanted to play from age four. Around 1970 I dived into the early music movement and learned to play a wide variety of renaissance instruments, mostly woodwinds. Before that I had also been learning electronics design, high quality sound reproduction, and computer programming.

I had a lot of choices of where to attend University, but in the end I was plugged into the Fort Collins science and arts scene. It was simplest to stay and attend CSU. I lightly considered a career in classical music, but believed my talent was more on the scientific side. Thus I majored in physics and worked full time as an operating systems programmer while in school.

While attending an inspired early music concert by David Munrow and his gang in 1975, I noticed there were microphones set up and discovered the campus radio station (KCSU) was broadcasting this and other concerts live. However their equipment and operator expertise was lacking. I was already building an inventory of high-end sound recording gear, and in 1976 made my first formal recording of an opera with a work friend. She had previously been recording other operas with a collection of her own and borrowed gear, and by pooling with what I had, we pulled off what I still consider today to be an excellent sound document.

This fueled a fire and with the income from my computer job, I assembled a recording studio (Pendragon) that focused on classical music combined with state of the art sound. I acquired only the finest microphones and designed much of my electronics, while modifying my professional Studer tape recorders to improve their sound quality. This meant I had a day job and a night job.

My work/opera friend was also responsible for digitizing atmospheric science flight data for subsequent computer analysis on a odd little minicomputer. As I accumulated recording equipment in 1976, I realized this offered an opportunity to convert old analog recordings from the 1920s-1950s and use digital processing to improve their sound. The minicomputer’s A/D converters were not intended for audio. They were only 8-bits, but ran at fairly high rates for the time (100-200 kHz). With my friend, we devised a scheme to digitize multiple, oversampled passes of the same analog recording, and digitally combine them into the equivalent of a 14-16 bit, 50 kHz digital system. I then wrote software for the university’s mainframe computers to perform the signal processing. The results were amazing, but we could only do short snippets of audio, given the minicomputer’s technical limitations and usage constraints. Someday I want to get back to ths, because I haven’t come across commercial systems that offer the same potential for improvement.

Before 1976 was over, I approached KCSU to suggest that I take over their live broadcast work. They were more than willing, as their talent generally wasn’t interested in classical music. However their weekday, 3 hour classical music program largely supported the station financially through fundraisers, and they needed a new host. So I also became their classical DJ. Within a year KCSU’s chief engineer quit. Stations were required at that time to have a properly licensed engineer on staff. Thus I was dispatched the following morning to Denver to take the FCC exam, and subsequently added the chief engineering job to my employment list, through which I endeavored to significantly improve the station’s on-air sound quality.

The state of live sound reinforcement in Fort Collins was mediocre at the time. The cultural authorities eventually persuaded me to expand Pendragon and take that over. I started in 1977 and built the largest sound company in the northern Colorado area. I custom designed virtually all the electronics and speakers that went well beyond anything else available in the commercial world.

I don’t remember when I met Bill Sharp at KCSU, but he was hosting their late evening, avant-garde music program. He asked me to engineer an experimental live recording session, which combined a range of local musical and spoken talent. That became our first album together (Mnemonist Orchestra). I didn’t play any instruments during that session, unlike what followed. The concept of melding non-classical and classical avant-garde music was appealing to both of us. Bill knew a variety of musicians and visual artists. I had access to classical musicians and a lot of different instruments, and was putting together a recording studio. Everything fit.

My interest in Mnemonists was founded on exploring a new basis for music, while not discarding lessons from the past, in terms of composition and organization. This included everything from the Renaissance era to serial and 12-tone music. My background in physics and the digital restoration of sound provided insights into signal processing techniques that were unconventional. At the same time I wanted to stretch the limits of recording technology to obtain the finest quality sound with tape and vinyl. I had nothing to offer on the visual art side of the process. Bill was much more interested in the integration of music and visual art. That was fine with me, but the other classical musicians and I viewed that as two largely independent efforts.

AC: Mnemonists emerged from Fort Collins, a university town around an hour north of Denver. Were you part of a broader subculture in that time and setting?

William Sharp: The local scene and - extrapolating across the globe - the pool of interested listeners was vibrant. As a collector doing radio shows, I encountered musicians and visual artists with great energy locally. Likewise, there was considerable enthusiasm on the west coast with Patterson's Eurock magazine and various mailorder firms that were bringing pressings into the States. On the east coast, it was Bley & Mantler's NMDS, with Feigenbaum's Cuneiform, Johnson's Forced Exposure, and important others soon to follow. This was rich fuel for independent productions on both sides of the country. In Colorado, we pulled together to experiment.

By the time 'Gyromancy' was in production, our own Dys label had acquired funding support from Kent Hotchkiss and the Aeon mailorder and distribution service that he founded in Fort Collins.

All part of the remarkable energy of that time.

Mark Derbyshire: There was a lot of music and visual art directly connected to the university, and a lot separated from it. I participated in small circles focused on avant-garde classical music, early music, and high end sound reproduction, but these were at best indirectly coupled to Mnemonists. My early music ensembles were busy with musicological research on compositions and contemporary performance techniques, and the wealth of musical colors, timbres, and textures that early instruments provided, compared to the more limited range of a modern orchestra. The classical avant-garde scene brought many well-known musicians and composers to Fort Collins to perform their works, with a nascent local effort. That was all acoustic and relied primarily on expanding classical compositional techniques. At least this set the stage for my musical explorations. A few of us were also searching for the best means to reproduce sound from a purely technical perspective, but that was only for traditional classical music. This was all in the same frame as Mnemonists, but there was negligible cross-pollination. Still, I was a product of all of these subcultures.

Through Pendragon I spent a lot of time with local classical and popular music. Because these folks fueled Pendragon’s progress, they ultimately made Mnemonists possible. While music students/faculty at CSU and local bands were never going to grow Pendragon financially, they offered ideal avenues to experiment with talented, willing, motivated, and patient musicians. This taught me nearly everything I know about recording technique, and encouraged me to develop the processes and equipment that maintained par with major recording studios, even if I didn’t have the millions of dollars they did. Especially I learned to avoid the serious technical and technique errors being made in those studios. I recently came across a detailed article on the struggles Steely Dan went through to produce 'Katy Lied' in 1975, ending up fully unsatisfied. They could afford and used the finest equipment available (they knew and bragged about this), but clearly had no clue of how to use it.

AC: Most listeners of 'Gyromancy' would be wondering what exactly it is they’re hearing. To pick out an example, there’s a section between roughly 11:00 and 13:00 of side B which resembles an orchestra gradually crescendoing. What were the underlying acoustic sounds here and how did it arrive in its final form?

William Sharp: I always opt for the mystery. There was a consistent intention to move beyond the literal nature of the source material and into a realm that was new and, perhaps most challenging, free from a sense of effects or outright processing. And, to accomplish this without synthesizers. To essentially transform acoustic sound.

Mark Derbyshire: There’s obviously a lot going on here. The instruments are primarily bowed classical strings, renaissance winds, and harpsichord. Other than the harpsichord, the instruments were played broadly and slowly with their intensity building the crescendo. Like much of 'Gyromancy', this was conceived in advance and some parts were written out. Our prior Horde effort had an overarching design, but it was more improvisational and stochastic in its conception.

The melodic and harmonic structures in this 'Gyromancy' section were provided by the musicians, with the rhythmic aspects more the result of signal processing. The tone colors were derived from off-speed playback of the original acoustic recordings with extreme and non-standard (and non-linear), modulated pitch-shifting with multiple loopbacks within the processing chain. This coloring varies according to the instrument(s), to make their disparate sounds blend in unrecognizable ways. Of course there is also straightforward echo/reverb added for atmosphere. Crafting this section was not particularly difficult, compared to other passages on the album.

The central technology tenets of 'Gyromancy' were we didn’t want the master tape to have more than one additional analog tape generation, and we did not use any multitrack tape recorders. The work was performed entirely on three highly modified two-track tape machines using a proprietary noise-reduction system I developed, somewhat related to dbx I, but more accurate and with minimal artifacts. Two of the tape machines used a fairly rare wide track format that required a full track erase head, precluding any track bouncing. These were run at 15 or 30 ips and the final master was 15 ips. The third machine was used more sparingly and had traditional two-track heads. It was capable of track bouncing, but we never used that.

The general scheme for the section in question, and 'Gyromancy' overall, was the acoustic and electric instruments were first recorded straight to stereo tracks. Depending on the ensemble, it would be mic’ed with a stereo pair (either spaced ORTF or X-Y coincident), or if necessary, individually mic’ed instruments. Electric instruments were generally DI (direct input), rather than mic’ed off an amplifier or speaker. Very clean sound was important at this stage, to support the upcoming signal processing. It normally wasn’t practical to perform the signal processing while the musicians played live, as Bill and I were often part of the ensembles, and it was more efficient to develop and tweak the processing without the constraints of tying up a group of musicians.

For the simpler sections, we would apply the signal processings to a played-back recording and print this directly to the final master tape. More complex sections required two recorders to simultaneously play back different tapes, with wild sync at best. These playback machines were both varispeed, which was integral in some cases to the resulting sound. In extreme cases we had a couple of digital delays that could capture and loop a limited amount of time (say 1-2 minutes) from a previous stereo recording. This gave us another layer or two if we needed it. In a few situations we processed a live acoustic directly from the microphones to the final master, if we wanted to maintain the highest possible sound quality. That was generally reserved for solos or small groups of instruments.

One of the challenges of 'Gyromancy' was assembling two apparently continuous musical pieces, one for each side of the album, from individually produced sections without adding tape generations. We employed a few well-placed splices, but we often mastered back-to-back sections by switching tapes and processing setups on the fly, using our one-of-a-kind mixing board. Such a process could be intense.

I designed our mixing board (and built it with a lot of help from Bill) to pull off complicated mixdowns entirely with live manual control. The board was fully analog with outrageously expensive, hand-matched field effect transistors constituting a transformerless and zero-feedback signal chain. The transistors required custom manufacturing runs that stretched the limits of what OSHA allowed at the time, because the parts contained highly toxic substances inside their hermetically sealed cans. I never found out why these parts were designed, but my belief was they were developed for a highly classified program by the US Government. However they came to be, they had a gorgeous, transparent sound that was far more accurate than anything else I heard at the time, or perhaps even since.

The board had no digital electronics, and intentionally could not be controlled by a computer. Everything had to be controlled by hand. It was a highly responsive instrument in its own right, and was capable of complex mixes that computer controlled boards of the time couldn’t touch. Fundamentally it had a 2 x 32 channel microphone/line input configuration, with 16 additional channels of line-only inputs. These 80 channels could be used to produce 24 simultaneous output mixes (combinations of stereo, mono, multichannel), or the entire board could be split in half to independently provide the same number of output mixes for each half, with the ability to crossfade any between the two halves.

This last bit was designed to handle all-day outdoor music festivals for Pendragon’s live sound reinforcement work. Festival organizers preferred no delays when switching bands, so while one half of the board was being used for the live speaker feed (audience), the other half was independently setting up and sound checking the next upcoming band. When it came time for the switch, one knob flipped the house and setup mixes via crossfades. With two performance stages or a stage split in half, changeovers could be instantaneous. We relied heavily on this capability for mixing 'Gyromancy' because we could crossfade between two different musical sections with completely different input/output/processing requirements on the fly. That saved a tape generation and/or a splice.

Tangentially the board also solved the problem of touring bands demanding that one of their roadies perform the house PA mix. In most cases these folks were woefully incompetent and would subject the audience to poor mixes and feedback, endangering Pendragon’s speaker systems and reputation. The board’s layout and functionality was unique, and in particular I skipped the cost and complexity of screening on any labels or scales for the controls. Thus the board was a giant mass of unlabeled switches, faders, and knobs. If a roadie dared to figure it out, I had a prepared lecture that described the board’s functionality in exhaustive and gory detail. That was enough to scare anyone away. Pendragon engineers always did the house PA mixes.

The 'Gyromancy' processing electronics were mostly digital, other than equalization which could be handled by the mixing board, and a limited use of analog dynamic range processors. We had a number of advanced digital units from Eventide, Delta-Labs, Lexicon, etc. Compared to what one sees today in DAW plug-ins, these ‘obsolete’ units provided more access to their internal, intermediate processing, which could be used to create highly unusual processing chains. I further modified some of these via hardware or firmware to achieve even more interesting sounds.

As mentioned at the outset, this was all designed to record sound in the best possible manner. Extended sections of music required multiple attempts to get one good final master take, mostly because of the complexity of making all of the adjustments in real time. Furthermore the digital processing was not always predictable and injected an element of randomness that sometimes worked and many times not. That added to the number of required takes.

Astute readers might suggest that multiple tape machines playing back to a master mix could have been equivalently replaced by a single multitrack machine playing through the processing to the master tape. However this wasn’t the case. Separate tape machines allowed the synchronization of the playbacks to be dynamically altered and performed with different variable speeds; doing this on a multitrack machine could not provide this freedom, or would have required additional track bounces, which would have added analog tape generations. Multitrack analog machines also had narrower tracks and were inferior in sound quality to the extra wide two-track machines we used. Digital tape machines at that time were still in their infancy and suffered from low quality sound compared to what could be done on analog. 'Gyromancy' could neither be made nor sound like it does in any other manner. It’s not clear to me that it could be done any better (or at all) with today’s modern tools. It was art and science possible during a window of time.

AC: Mnemonists are said to have split into the musical group Biota and a visual-arts collective still called 'Mnemonists'. I'm curious, first is that accurate? but also, about the role of visual arts in your work more generally. And I’ve always liked 'Gyromancy's cover, could you tell us about this artwork?

William Sharp: Biota evolved as a separate entity from Mnemonists, with the two groups overlapping somewhat in membership. We united for a commissioned performance at New Music America in Montreal. A core of visual artists that worked on the Mnemonist projects continued to contribute to the Biota releases under the Mnemonists moniker. The Biota name entailed a significantly different approach to studio work (e.g. involving multitrack) while the Mnemonists' visual philosophy never changed. (The latter's work permeated the Biota studio environment.)

In significant cases, there was a useful dialog between the sonic and visual contingents, with one influencing the other. Tom Katsimpalis's comments on the front cover imagery follow...

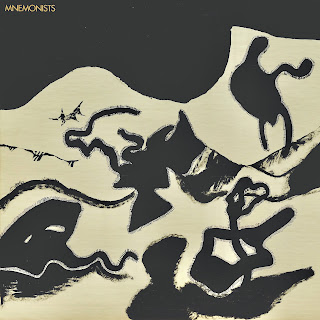

" Akin to the the uncharted musical terrain of Gyromancy, the cover art flows from the unconscious development of imagery related to the title’s definition.

(In part: '...a person would continue the activity

until an intelligible sentence, or until madness

intervened. The dizziness brought on by the

spinning or circling is intended to introduce randomness

or to facilitate altered states of consciousness.')

In this space, animalistic, biomorphic,

and imaginative entities cavort in a state of

of suspense. As always in my work,

the image is left open to interpretation. It draws

upon the power of creating mood to enhance

the aural experience.

The monochrome approach for the image

is an homage to black and white photography,

film, and the printed word. "

Mark Derbyshire: Bill and I have different opinions about this. It revolves around questions of what is Mnemonists, what is Biota, and what is the relationship between the music and visual art for those projects? These are questions with multiple answers, depending on the particular group members.

Bill and I never saw the same relationship between the musical and visual aspects. Bill believed in the importance of integrating the two. I never saw much beyond a contrived connection, and to be callous, the visual part often appeared little more than cover art on an album to me. We weren’t doing avant-garde musical theater or opera where the visual and musical aspects were intertwined.

'Gyromancy' was an experiment in efficiency compared to our previous Horde project. The former was time consuming and exhausting, leaving an enormous pile of tape recordings we never used. 'Gyromancy' was still a monster, but there was less wasted effort and a focus in driving towards an intended sound or goal, rather than trying out a lot of ideas in search of something we liked. I didn’t view 'Gyromancy' as the end, and it wasn’t, because we got back together for our live performance in Montreal in 1990. But we needed a break, which became more of a conclusion.

Shortly after 'Gyromancy’s completion, I finished my studies at CSU, ran out of challenging jobs in Fort Collins, and moved to Denver to pursue a real career. I kept running Pendragon, but at a drastically reduced level. Pretty much any remaining classical musicians were similarly moving on. None of this was new. With the exception of a very small number, most musicians came and went all of the time.

Following 'Gyromancy' there were still musicians and artists in the collective. My sense was they wanted to pursue a different musical direction that didn’t match where I wanted to go with Mnemonists. So they coined themselves Biota. While they were kind enough to continue crediting me in some capacity, it wasn’t my music and I wasn’t participating. The other classical musicians and I still saw Mnemonists as a group and musical concept to which we would eventually return and continue where we left off.

For whatever reason Bill and/or the Biota members chose to redefine Mnemonists as only the visual part going forward. That came out of nowhere. None of the classical musicians were consulted and we were not in agreement. There was no continuity from Mnemonists, the music, to Mnemonists, the visual art. For the Montreal concert this conundrum was further complicated by concatenating the two group names. That may have satisfied some members or a marketing motivation, but I didn’t fashion myself as having any hand in Biota, and the music we composed and performed in Montreal to me was strictly an extension of Mnemonists, the music. I did not see anything connected to Biota.

There was live visual video during the concert. None of the classical musicians ever saw it or had anything to do with it. Were those visuals an attempt to interpret/complement the music or to conceive something independently? It certainly did not feed the music or inspire it, and the two were not collectively developed. The music was abstract and I saw no value in trying to visualize or supplement it. To me, conflating the music and visual art served mostly to distract or mislead listeners.

William Sharp: The trip to IAM studio in Irvine was specifically for the cutting of the lacquers. 'Gyromancy' was mixed live in the Colorado studio utilizing multiple, significantly modified two-track machines. None of this could have been achieved in a remote location without extensive rehearsal such as that required for the Montreal performance.

At the lacquer cutting stage, we felt it advisable for sonic accuracy to play back the 'Gyromancy' master tape with the exact machine and NR decoding that was used to record it. Thus, the trip to California. Once the lacquers were cut, we quickly hand delivered them to Record Technology in Camarillo for plating. I remember the California trip as a very economical journey with a singular purpose: no compromises with the sound.

The other problem I had with previous Mnemonists albums, and others I engineered, was the cutting studios simply didn’t have the quality of equipment we were using. They also didn’t have the proprietary noise reduction system I developed, so there was no technically accurate way they could play back our master tape. The solution was to pack the same tape machine and noise reduction unit, that recorded the master tape, into a car and drive to Los Angeles. Both Bill and I worked non-music, full time jobs, so we had to schedule a session on a weekend and drive there and back.

The driving time for such a trip, with the speed limits then in force, was around 20 hours straight through each way. Just to make this interesting I had purchased a car that allegedly could get 67 mpg on the highway. It didn’t and I discovered the manufacturer was selling a different version in Colorado because of the high altitude. The gearing had been changed along with the engine tuning. This irritated me to no end, so I ripped out the transmission and differential and rebuilt them, with a bunch of parts cobbled together from other similar transmissions, into an even higher mileage version than was sold in the low altitude states.

This trip became an acid test to see what mileage I could achieve in a round trip, with a substantial amount of altitude variation driving up and down the Colorado mountains. The other challenge was to get to LA and back on two tanks of gas. On parts of this route there were signs that proclaimed, “buy gas here because nothing is available for next 100 miles”. This got a bit ticklish because the gas gauge hit empty earlier than expected, even though I was shutting off the engine for any meaningful downhill coasts, and was employing a number of custom gauges to help maximize our mileage. We pretty much arrived in LA on fumes, but we made it and over the round trip achieved 75 mpg. This added an extra level of tension to a studio-scheduled arrival time in LA. Bill quite rightly wasn’t terribly amused by my little side games.

Anyway the lacquer cutting was uneventful. I insisted the noise reduction unit outputs be plugged directly into the cutting head amplifier, which removed all the unneeded gear that otherwise would have modified the sound. Our cutting engineer was a fish out of water with all of his “safeties” removed, but he soldiered on and squeezed all the level possible into the cut. We grabbed the lacquers and rushed off to the plating plant on the other side of town, which processed them immediately according to prior agreement. If you don’t do this within the first hour or so, the plating quality suffers. All that was left was an immediate 20 hour drive back. We got an hour or two of rest when we arrived in LA, but that was about it beyond trying to grab sleep on the road while the other drove. I couldn’t sleep like that.

AC: Mark, you mention that ‘Gyromancy’ was “designed to be heard best in the future, and not at the time of its release”, due to the technological limits of transferring from the master tape. Here we are in the future, would you say there has since been an effective transfer?

Mark Derbyshire: 'Gyromancy' was conceived to push the limits of the analog tape system I had built. There was no way a vinyl record would be able to reproduce it. Even today the master tape pushes the limits and technical limitations of the best digital systems. However it was recorded on an early 1980s tape formulation that is highly vulnerable to ‘sticky-shed’ degradation, which afflicts most master tapes from that era. In the worst case the oxide layer, on which the sound is recorded, completely falls off the tape, rendering the tape useless. Even if that doesn’t happen, the tape can be very challenging to play, because the binders that hold the tape layers together tend to absorb water over long periods of time. They turn into a sticky goo that makes it hard to play on even a top drawer tape machine. The industry’s solution is to bake such tapes in a tightly controlled, low temperature convection oven. This causes the binders to reform and evaporate off some of the water. Such tapes can be played for a period of time before the process has to be repeated.

Fortunately the Pendragon masters have been stored in a cool, dry environment and required only a minimal amount of archival restoration. I made the first 'Gyromancy' digital transfer in 2000 using one of the finest A/D converters then available, with 24-bits at 48 kHz. I carefully compared the sound from this process with what was coming off the analog tape – it was pretty close, but consistently not identical. I’ve auditioned other A/D converters since then that didn’t do even that well on other master tapes. In 2022 I acquired another A/D that sounds closer to the original and made another 'Gyromancy' transfer at 24-bits at 96 kHz. It could have been done at 48 kHz and still sounded the same, but 96 kHz is now the de facto standard and doesn’t cost anything in terms of quality or money. There was limited physical deterioration in the original 'Gyromancy' master tape since 2000, and if this transfer were to be released, I would consider lifting tiny sections from the 2000 transfer to cover minor blemishes in the one from 2022. Still, there is no question the 2022 transfer is better, and is not likely to be further improved upon.

I have no confidence that a SACD would approach the quality of our latest transfer because it requires a lossy conversion process and does not achieve a consistent sound quality. Hypothetically 'Gyromancy' could be released as a high resolution digital download or an audio-only Blu-ray disc, and provide listeners with the same sound quality I hear off the 2022 remaster and close to what Bill and I experienced in 1983.

High quality sound is a victim of the cell phone era. The top recording studios have been in trouble for the past 40 years for other reasons. Decent quality recording equipment at an affordable price can now make a hit recording for any band on a budget, but this is a far cry from the quality of what could be achieved in the pre-digital days of the 1970s. In many cases one can no longer buy the necessary equipment new that was once available, particularly with regards to microphones. This regression is a source of sadness for me.

AC: You’ve both spoken fondly about the live reformation of Mnenomists at a 1990 music festival in Montreal, describing it as a high point for the group. One thing I’m still wondering about that - what was the audience reception? Generally speaking how have people reacted to your music over the years?

William Sharp: My impression from stage was that the audience was hushed until the last moment. There was a lot going on. Similar to the 'Gyromancy' concept, the audio did not necessarily match what the audience was observing instrumentally on stage. All electronic processing was live, there were no synthesizers employed, and there were no prerecorded tapes rolling. Further confounding the experience was the fluid and highly abstract video imagery projected onto a large screen above the stage by Heidi and Richard Eversley. In all, I think the performance was well received.

Over a decade later, we were pleased to work with Eric Lanzillotta at Anomalous on a CD release of the event. Entitled Musique Actuelle 1990 (NOM25), it includes the full program drawn from the most successful segments of our live and rehearsal recordings of the commissioned work. The visual package includes stills by Heidi that are derived from the footage screened during the performance.

Mark Derbyshire: Montreal became the culmination of what we could achieve with the Mnemonists’ compositional and performance methodology. It almost didn’t happen when the equipment got stuck at the Toronto airport in transit during a snowstorm. But it arrived in the nick of time and we were able to set all of it up, and even squeeze in an onstage rehearsal.

Compromises must always be made, particularly for live events. All sounds at this performance were generated onstage by the musicians, mostly acoustically, without any synthesizers or pre-recorded sounds. We had been worried the hall would not provide real tubular bells and were prepared to use a sampler in case they didn’t come through, but they did. Clearly we couldn’t make stereo recordings during the show and play them back through processing, as was done for 'Gyromancy'. But we had enough musicians so this wasn’t a limitation.

We used the same mixing board as for 'Gyromancy' and pushed it to its limit. All of us played instruments, while a few of us shared mixing duties. We were spent when it was over. The cue sheets for that performance fill a binder, as we constantly had to readjust and reset the processing units and board throughout. But it was all done by humans. The signal processors were in some cases the same as we had used in 1983, but many were new or improved.

I wasn’t in the audience and it’s impossible for me to assess how they experienced the show. But what they heard was close to what we intended. The house mixer had little ability to modify anything, as we only provided them with a stereo feed. Everything was mixed onstage by us. Before the performance started it seemed many listeners had no idea of what they were about to hear. Afterwards many weren’t even sure what they heard. We did get applause. Some of the other performers at the festival couldn’t connect with our music. They were more traditional in the “new music” sense, and frozen in time. I liked their music, but I’d heard the same style and some of the exact same pieces 20 years earlier. We recorded the concert to DAT (out of necessity) and it can still be judged today. This performance may lack some of the depth of 'Horde' and 'Gyromancy', but it demonstrated a direction beyond both. It’s sad we didn’t keep going. At least not yet.

I’ve been surprised over the years with the staying power of Mnemonists in the small circles of those who pay attention. It’s gratifying to hear or read reviews/reports that recognize we were working in a unique world. A number of those listeners get what I was hoping to convey. Certainly many feel the need to describe what they hear in visual terms. I can’t really blame them because our albums provided an illusion that somehow the music and visual art were connected, and the first three albums suggested post production titles for the individual pieces/sections. I don’t believe any of this was consciously or subconsciously in any musician’s mind while we were recording and this should have been made clear at the time. Still, there are plenty of other listeners who dive in to understand the musical details and ponder how the sounds were conceived or produced. Involving listeners, rather than reducing them to observers, was always my intention.

William Sharp: It is gratifying to learn of this effect on listeners. I think it is a common goal with many who experiment with sound: a desire to create something that mimics the barely expressed or unwitnessed. It could be a mental image, a landscape, or a sonic profile that we envision but are challenged to convey to the listener with reproduction technology. In the case of 'Gyromancy', the process was multi-layered with significant forethought as to how the technical challenges would be met. When we learn of these responses in listeners, we feel a degree of success.

Those who have inspired me over the years are each on their own planet. I can only visit their haunts, it seems. I have tried to move off into my own world for production, if not completely free of those influences. We all share a bit of that wavelength you mention. Chris Cutler and many of our labelmates at ReR immediately come to mind. The label’s early support for 'Horde' and 'Gyromancy', and later for Biota, has been essential fuel for my creative process. Top of my list.

Mark Derbyshire: Offhand I can’t think of other artists I know who were on similar paths to Mnemonists. Many avant-garde musicians were understandably trying to make a living off their work and fell prey to commercialization pressures. Those who didn’t often stayed in well-defined boxes. Biota was a different animal, although equally valid to those it touched. Because there were musicians common to both groups, it had similarities to Mnemonists. However it sounded to me as intended to appeal to a larger audience, with the attendant compromises and constraints in its musical language. It wasn’t a evolutionary successor to Mnemonists, the music.

The Earth is a big place with many explorers. I’m still captivated by composers who took risks to achieve their vision. Some are highly recognized today, such as Mahler or Ives, neither of whom was well regarded as composers in their day. Composers such as Webern, Schoenberg, and Crumb were more risqué. There were oddities like Gesualdo, who wasn’t someone I’d ever want to meet, but who conceived a dissonant musical language centuries before anyone else dared. There are musicians who rediscovered long forgotten compositions we revere today, and the early music proponents 50+ years ago reawakened the sheer joy of music from the times of the Renaissance. You don’t have to search for weirdness to appreciate and assimilate the range and history of the human experience.

AC: Please tell us about the other players on 'Gyromancy' - Steve Scholbe, Amy Derbyshire, Karen Nakai and Mark Piersel.

Mark Derbyshire: I can only report on my sister, Amy, who is still busy doing her thing. In many ways we shared very similar experiences growing up and branching out. I was more into sound and she was more into lighting and technical theater. Still we worked together very closely outside of the performance arena for many years before we separately settled down.

William Sharp: Steve is an original member of Mnemonists. He was an important early influence on my music education during our teens. Serving a multi-instrumental role, he began with reeds and experimentation with electric guitar feedback. Later, his contributions expanded to include acoustic guitar, the Uzbek string rubab, and compositional and production work in Biota.

Karen worked with us on bass guitar during Mnemonists' first live performance at the Colorado State University art gallery in 1981. This was in support of Mnemonist James Dixon's graduate painting installation. She was also involved in rehearsals circa 'Gyromancy' for a planned Mnemonist gig in Nebraska that never transpired.

Guitarist Mark Piersel joined us at the suggestion of Joy Froding, the late Mnemonist painter who contributed so heavily to our visual aesthetic. Mark's role later expanded significantly to essential production, engineering, and composition in Biota.

AC: Do Mnemonists… still exist? Or do you regard the project as something from the past? What are you both up to nowadays?

Any final thoughts for our readers?

Mark Derbyshire: I’m still doing the heavy lifting physics/mathematics/computer work for which I left Fort Collins, but in a very small company that avoids large corporation mentalities. I’m also running a number of sound projects. Many involve remastering recordings I did long ago, but I’ve been making occasional new high-end recordings to keep in shape and stay motivated. My hope is to have the relevant archival projects completed within the next couple of years. All of the Mnemonist master tapes have been recently re-transferred, as described previously for 'Gyromancy'. Bill and I haven’t discussed any release plans, mostly because the mediums commonly available today may not be the best matches for our material.

I just finished a major microphone modification I had wanted to start in the early 1980s and I’m working on designing significant audio and video upgrades for my listening and theater environments. My wife and I remodeled our house a few years ago to be completely carbon negative, and we’re starting a project to expand it to have room for our upcoming new adventures. I have a lot of musical instruments to relearn and a performance/recording space on the drawing board. If this turns into an ensemble of any form, I’m game. I’m not planning on slowing down voluntarily.

I always assumed, or at least hoped, Mnemonists would become active again. I’m beginning to have doubts that will ever happen. I’m not interested in repeating the same things we did before, but I’d like to get back into that creative groove, whether or not anyone else cares or listens. We’ll see.

William Sharp: Mnemonists theoretically do still exist in the sonic realm. The instrumentalists and visual artists alike are scattered now but remain in contact. Mark Derbyshire and I talk of sound from time to time, attempting, as with this interview, to maintain clarity on what transpired some forty years ago. Mark has made much progress over the last decade with preservation and archiving of our masters. Ultimately, this experimental drive remains with us.

AC: It's great to know you're out there! Thank you both for talking to me.

Mnemonists can be found at http://www.biotamusic.com/.

Images

0) cover image by Tom Katsimpalis.

1) Artwork by Dana Sharp.

2) KCSU March79: shot through the monitor window at KCSU studio during the session for Mnemonist Orchestra (DYS 01, 1979). L-R: Scholbe, Relic, Yeates, Foreground: Ragin, Mowers.

3) Artwork by Joy Froding.

4) Artwork by Carol Heineman.

5) Montreal setup: obscurely pictured is the custom board transported from the studio to the venue. Sharp, Derbyshire, center. Whitlow, right.

6) Attributes 2: session c. Oct 79 - Feb 80. L-R: Scholbe, Yeates. Background: Ruth Hougen at the harp. Photo credit: Bruce McGregor.

7) Artwork by Heidi Eversley.

8) Artwork by Savic Enn.

9) Artwork by Carol Heineman.

10) Artwork by Randy Yeates.

11) Derbyshire Attributes: Derbyshire at a session c. Oct 1979 - Feb 1980 for Attributes. Mixing equipment predates that of Gyromancy. Studer reel machine in foreground was central to Gyro. Photo credit: Bruce McGregor.

12) Artwork by Tanya Staab.

13) Artwork by Heidi Eversley.

14) Artwork by Carol Heineman.

15) Montreal street: L-R, Scholbe, Sharp, Piersel, Derbyshire.

16) Artwork by Dana Sharp.

.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)