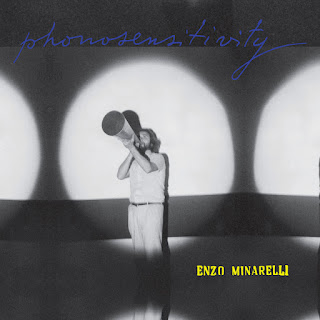

Enzo Minarelli: Phonosensitivity

Navel-Gazers #36 is an interview with Enzo Minarelli who is going to talk to us about the Phonosensitivity collection on Pogus records. Consisting of 10 “sound-poems” recorded between 1979 and 1987, this is no ordinary spoken-word collection. It’s one of those deep explorations of the human voice on tape, reminding me of similar experiments carried out sporadically since the 1960s by figures such as Bill Bissett, Lily Greenham, Jaap Blonk and others who’ve not only committed voice to tape but really embraced the vast possibilities of the medium. Over the course of these pieces Enzo’s sound-poetry - which is multi-lingual and even extra-lingual - is subject to every conceivable treatment from layering to panning to distortion to delay to speeding up and slowing down and everything in between as he barrels through like a windmill in a hurricane, spewing surreal verbiage of all shapes and sizes. Enzo seems like quite a talkative fellow, which is always good for these interviews. I want to ask him not only about the pieces themselves but also about the era in which they were created, when home recording, while not quite the common facet of life it is today, was starting to become more accessible for many artists around the world. Let’s get ready to talk!

AC: Thanks for joining me on Navel-Gazers! Before we talk about 1979-1987 why don’t we start earlier.. what kind of upbringing did you have? Do you remember when you first did anything artistic?

Enzo Minarelli: My first attempts at sound poetry date back when I was in my teens (mid sixties), as my father gave me a crazy present, a Geloso wheel tape recorder. I started immediately to play with that odd object, attracted by the microphone. Listening today to those naive recordings, I can only laugh but in a way it was the origin of my future experiments, which of course at the time I was not conscious about. Parts of these pieces can be heard in the soundtrack of a videopoem of mine, Wow Flutter Stop (1984). My beginnings were literary, and my University degree was in Venice (the famous Cà Foscari). I graduated in Psycholinguistics and learned three foreign languages, English, Spanish and French. Let me also say that during the writing of my first linear books I perceived the importance of sound. No doubt hearing my own voice recorded at the age of thirteen was a sort of panacea, a shock in a way, as I immediately perceived the voice as a body, as an instrument, as something outside me but at the same time inside me. A decisive experience and also really educative, as through the voice you know exactly what kind of person you are.

My first linear book Obscuritas Obscenitas (1979), a booklet with a little bunch of poems, got the attention of an important Italian critic, who was compiling in that period an anthology of Italian literature. Included in it was a whole section of my book. So, after the first book was issued I found myself, unknown and young, gathered at the top with all the famous Italian poets of the vanguard. Linear poetry no doubt but I was already aiming at sound. Some decisive readings of La Divina Commedia by Dante, and of Joyce, Pound and Edgar Allan Poe pushed me definitively in that direction. My first official sound poem was Il Poema Spettacolo (1979), the first live execution of which was in a small theatre in Bologna (now destroyed) lasting 20 minutes. It was a performance in my future style of Polypoetry as there I was on stage performing the text live with a couple of musicians, a couple of dancers and with many images on screen. It can also be heard today - over the years it has been reduced to the current 5 minutes, but essentially it is the same old structure. The title is simply “Poema”, and it’s one of the most performed throughout the world in my career.

AC: How remarkable that hearing your voice on tape was the first moment you conceived of it as an instrument.

Enzo Minarelli: The point is that in art, the artist must be conscious, or intentional as John Cage used to say. Those experiments when I was 13 or 14 years old were interesting as I did not use the tape recorder only to record songs but also to know my voice. I can't define that as a work of art. It is just like a child who starts walking, he is not walking, he is simply moving, tottering.

AC: Could you explain these terms: sound-poem, polypoetry? Why don’t you consider your early experiments with the Geloso sound-poetry? Were they of a different nature or is it just that they weren’t fully realised?

Enzo Minarelli: Sound poetry is referring only to the ears, it is an oral experiment using the voice applied to words, or not to words. Polypoetry is a manifesto I wrote in 1987, where I developed a theory about the performance of sound poetry. Polypoetry must be live and you watch it just like a show. That means that behind it, one must always have a theory, which is why I don't like for it to be improvised or instinctive. In both cases, there is not a trace of writing. A sound poem can only be heard, and Polypoetry can only be seen. In this sense these experiments go beyond writing.

AC: It reminds me of something I was planning to ask you. These pieces on ‘Phonosensitivity’, have they ever appeared in a live performance (I guess that is to say Polypoetry?) context in any form?

Enzo Minarelli: First of all, there are poems which can be performed live and others not: it depends on many aspects - the structure, the technology, its feasibility and so on. Just to go where your question is going, only Kandinsky and Con Sonante were performed live, the first in Polypoetry 1 (1982-83), and the second in Polypoetry 2 (1985-86). As you see, I use these progressive numbers for all my live performances. They were performed with other poems, of course.

‘Kandinsky’ is special piece, as for the live performance I used some objects and a coloured balloon where I first scratched in rhythm the linguistic development of the double couple red-green / yellow-blue, then I made it deflate, addressing the flow of air and directing it towards the microphone. I did all that just to get a dark effect almost impossible to reach with those poor analogical instruments of the times. ‘Con Sonante’ is an attempt to make the consonants not only sound but also speak. I mean that through the simple power of each consonant I can communicate a lot. Just listen to that piece and you will understand immediately what I mean, sometimes you simply need a phoneme sounded out, which counts much more than a lot of sentences, the power of synthesis in a way.

Deserving a discussion of its own is Québec smack, a unique performance of mine involving a group of people on stage (among them Philip Corner, Richard Martel...). It was performed at the Intervention Festival, in Quèbec City in the mid Eighties. I was playing the role of orchestra director and each time I addressed one member of the chosen group he had to repeat his name, then his surname etc until I threw myself towards them shouting "Noi chi siamo?" (Who are we?).

AC: Let's talk more about the 'Phonosensitivity' pieces. Are these all of your productions from the time period, or is it a selection of your favourites?

Were they recorded in a studio with an engineer or were they home recordings, or what?

Enzo Minarelli: It is a selection of poems produced in that long ago but indeed very prolific period. The publisher wanted unissued pieces from my early career. I chose ones which represented either my research around the concept of destruction-construction of the word, or my typical way of digging into a single term (see Kandinsky), or just using a single word as a complete poem (see Poems In Word). Let me spend a few more sentences talking about that magical decade, let’s say the end of the seventies/ end of the eighties. I remember I was completely absorbed in my work, all day and part of the night too, it was a sort of incessant, creative furor. I bought with the little money I had at that time a Revox professional tape recorder, and all the pieces you are hearing on the record come from that hardware. No doubt it sounds obsolete if you compare it to the digital excess of today, but experience says that what counts more is not the machine but the project to be developed.

AC: A couple of the pieces have musical instrumentation - thinking of ‘Con Sonante’ and Correspondance pour Le Corbusier… were there other players involved? You mentioned ‘Con Sonante’ was performed live, would that have included the instrumental accompaniment? What’s your take on music, what sort did you like at the time and what sort do you like now?

Enzo Minarelli: In the case of ‘Con Sonante’ it was a local rock group. I tried to direct them as they were too rock-addicted. They were not a professional group, unlike other musicians I would collaborate with later, such Ares Tavolazzi (of the band Area) or Enrico Serotti (of Confusional Quartet). When I performed that piece live I was not with players on stage but I used a pre-recorded track with my own live voice. In the other piece, ‘Correspondance pour Le Corbusier’, the music was made by myself using a synthesizer I bought in Canada in the mid eighties.

As far as music in sound poetry is concerned, let me say that a sound poem is generally not a song where the music should be overwhelming. In sound poetry the voice, the orality, the vocality must be the first point to be developed, so all the other elements of the so-called live show, music included, must be put at a secondary level (see point 6 of my Manifesto of Polypoetry). If you listen to other pieces of mine such as Poema, Regina, Monostico or Nordsud & Sudnord, you will realise what I am saying. I am using music but in a way that does not disturb the main stream of the voice, just like a shade, a mere hint.

About my musical interests, since forever I am open to any kind of music, from classic rock music of course to opera, from madrigals to folk music, from Carmina Burana to pop music of the Sixties. As you can see I have not a favourite. If I had to say only one, I should choose lieder.

AC: In our introduction I mentioned a few other recording artists whose work might bear some resemblance to this Phonosensitivity stuff. At the time, did you think anyone had ever done anything similar? What about in the years since? Do you ever hear something and think: this is like what I was doing with those recordings in the 80s?

Enzo Minarelli: No, during the composition of those pieces I knew none of the poets you mentioned. Of course afterwards I got familiar with them. Personally I got friendly with Jaap, we’ve known each other since the early Nineties and have performed many times together in festivals throughout the world. The last time we met was in San Francisco, 3 to 4 years ago at a large festival dedicated to sound poetry.

Now, about those other questions of yours, there is a clear premise to be stated here: nobody invents something new. At least, this is my deep belief. What one invents is a style, a way of expressing oneself. I know I am working in a field where many others are pursuing their own target and we are racing along parallel lanes. Apparently all is equal, but if you look and listen carefully, you will see great differences among us.

Take Jaap again just as an example, he has a powerful voice, and all his work pivots around this. For example he is a marvelous performer of Ursonate (Kurt Schwitters). In my case, I have not a strong voice, just his opposite. I have to pay a lot of attention before every performance, especially if it exceeds 30 minutes because the risk is to lose it in the middle of the show, so I have invented some personal exercises I practice off stage. Aside from this, my work develops the linguistic side much more, and moreover I use video images, and so on. The world of sound poetry is very simple in a way, but what counts is setting up a personal style.

Anyway just to answer you, one of my main targets when I started this job called being a poet, was to be original or at least to create a shape which makes one say a few seconds after the piece has started: "this is Enzo!".

Your last question would need a book to be answered properly. Yes many times, too many times, I am hearing things which are similar if not the same as what I have done over the past decades. The issue is that today technology is cheap and everyone can have access to great hardware with little money. On principle this is positive, let's call it the democracy of technology! However you need a couple of essential considerations a priori: first, one ought to study and learn and be educated about what came before, otherwise the research does not improve. And secondly before creating, one needs to produce a storyboard. Or pattern execution as I would call it (just to avoid the term “score” which is too connected to music).

AC: I agree - yeah the tech has become accessible, great but it doesn’t exempt the artist from having some substance behind their work or situating it in context.

Well Enzo, I must say it’s been great riffing with someone who shares the gift of gab. You are surely, to quote The Maltese Falcon, “a man who likes talking to a man who likes to talk,” so thank you!

Enzo Minarelli: Well, good answers always depend on good questions - it’s also been nice from my point of view. What we said about technology must also be applied to the so-called "expert journalists" who come and interview me only after reading some quick lines on the web without having listened to anything! Luckily this was not the case here as I sensed in you a deep knowledge of the items discussed, along with an attraction towards my work.

AC: Do you have any current projects you’d like to promote or further thoughts or comments on ‘Phonosensitivity’ or anything else for our readers?

Enzo Minarelli: Yes just to conclude, let me mention the latest LP which has been issued, De Revolutionibus. Many of the concepts discussed during this interview will be useful for its listening. Then EDUEL (Brazil), a University Press, are publishing Vociferazioni, the orgasm of voice,1978-2019, edited by Frederico Fernandes, along with a video collection of all my pattern executions which is a historical work worth seeing. And finally within the year another LP, La Stanza sul Fiume (The room on the river) developed with a great Italian musician, Enrico Serotti.

AC: Eccellente, thanks Enzo!

Enzo can be found at his website https://www.enzominarelli.com/.

Images

1) Sound Studio, 80s

2) Kandinsky, 1980

3) Sound Video Archive

4) Onoma, 1982-84

5) Kandinsky, 20 nov 1981, Crema

6) Il Poema Spettacolo, Il Teatro delò Guerriero Bologna, 1979

7) Metallofono-Diario Come, 1982, Sala Po