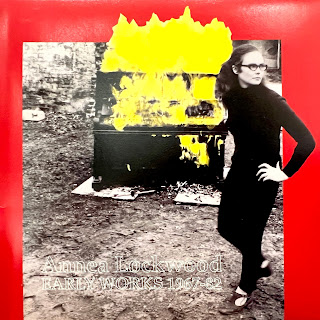

Annea Lockwood: Early Works

Navel-Gazers #40 is an interview with Annea Lockwood who is going to talk to us about the Early Works collection on EM records. A trove of historic material dating back to as early as 1967, it contains one-full length album (The Glass World of Annea Lockwood) plus the hypnotic, singular piece ‘Tiger Balm’, in addition to a special insert chronicling Annea’s famous Piano Transplants performance art installations from the period. It’s only the tip of the iceberg when it comes to an artist who has been exploring sound - from every conceivable angle - for over half a century, and yet to my ears this is really the perfect point of entry. I want to understand the origins of Annea’s practice. What were the original ideas, the experiments which ushered her into that idiosyncratic world of sound-maps and sound-balls and flaming upright pianos… 11,784 miles from her home city of Christchurch, New Zealand? I want to know more about the journey from country to country, from river to river, from the glass worlds to the floating worlds.... in fact maybe it’s best that we’re focusing on those specific years - 1967 to 1982 - otherwise there would simply be too many questions to ask Annea Lockwood! Ok, let’s see what she has to say…

AC: Thanks for joining me on Navel-Gazers! I have to confess that part of why I wanted to discuss your early works is I am a “transplant” myself, in London from New York - whereas you appear to have been London-based in the 60s before relocating to New York in the 70s so I’m quite interested in that aspect of your biography. Am I right in assuming ‘The Glass World…’ was recorded in London? What do you remember about that? What do you remember about London generally at that time?

Annea Lockwood: I lived in the UK, mostly in London, from 1961 until I moved to the US in 1973, with the exception of a year I spent studying with Gottfried Michael Koenig, a superb teacher, in Cologne and Bilthoven (at the EMS studio) from 1963 – 64. I started performing my Glass Concerts in 1967 (began working with glass in ’66) and the very enterprising record producer (the Tangent label), Michael Steyn, came to an early performance in London at Middle Earth, was intrigued and asked if I’d like to record it with him.

The record, Glass World of Anna Lockwood, came out in 1970, but we started recording in 1968, possibly even in ’67. It was a luxuriously leisurely process because I was giving performances of Glass Concert frequently up until the final NYC performance in ’73, and kept discovering new forms of glass, new sounds throughout that time, which we recorded. Mike was a superb engineer and the experience of working with him was one I treasure still. Among other things I fell in love with his gear, especially his Nagra – an obsession which I could never afford to fulfil. We recorded rather late at night in a small church with very fine acoustics in London, accumulating a large pile of tapes, then in ’69 we started selecting and editing. Glass World has been re-released twice since then, first on EM, then, in a facsimile edition by Steve Waskovitch for the Superior Viaduct label in 2017.

It was a great time to be working as an experimentally-minded artist in and around London: waves of genre-breaking artists were continually passing through and I got to know some, for example Carolee Schneeman and Henri Chopin, then living in the UK. I met the Sonic Arts Union foursome, who became good friends, and the Musica Elettronica Viva musicians, (at that time only other sound artists I was aware of, besides the Baschet brothers, who were also using glass); the Living Theatre came and went; I met Kosugi and loved his work, so it was an honor to be able to work with him and with John King on Jitterbug for the Cunningham company many years later. Merce Cunningham, David Tudor, John Cage, Morton Feldman, were also frequently in London and, like those I have mentioned above, opened many doors for me aesthetically and in other ways. A close friend and cherished influence was the English composer and writer, Hugh Davies, who can be seen in some of the images of the first Piano Burning and whose Shozygs and other work is archived at Goldsmiths College.

Then there were the sound poets, a thriving scene at that time especially: Bob Cobbing (with whom I worked in the mid-sixties), Lily Greenham, Sven Hanson, Jerome Rothenberg, Lars-Gunnar Bodin, Henri Chopin as I’ve mentioned, Bernard Heidsieck, and the Fluxus artists whose often-playful work rhymed well with my own delight in sheer play.

In those years, initially through the publication Source: music of the avant-garde, I also met Pauline Oliveros who became a good friend and major mover-and-shaker in my life: it was Pauline who started the process by which I ended up in the US in ‘73, recommending me to the composer Ruth Anderson as a substitute teaching in Ruth’s EMS at Hunter College (CUNY) while Ruth was on sabbatical, thereby transforming my life – musical and personal. Pauline introduced me to many in the new music scene; we performed one another’s scores - a powerful form of affirmation, exchanged many letters, and then, much later in 2005 she and her spouse, Ione, encouraged Ruth and me to follow their example and get married in Canada after many years of living together.

Talking recently with sculptor and sound artist Liz Phillips, who was moving in similar circles in the States then, we found that for both of us the sixties was a crucial period which freed us: for example, I felt free to explore in any direction, in any medium which fascinated me, and devising my own aesthetic by simply doing. My rule of thumb was to follow up on the most extreme ideas which came to me, knowing that would open new pathways. The place and times gave us room to do just that, and - which is of course essential, venues and situations in which we could present what we discovered. It was such a fundamental gift, formed by community.

AC: Sounds like a magical time!

Let’s talk more about the glass. How did you first get interested in glass and what drew you to it? Where would you find it? Were you collecting it? Also glass being fragile, just curious about the logistics of moving it around… you mentioned a final concert in New York, did you lug a bunch of glass over on a flight?

Annea Lockwood: I was proposing that acoustic sounds, listened to individually, often have intricate inherent structures, the details of which are blurred when we string them together as music; which is what I’m referring to in my sleeve notes on ‘Glass World…’. This train of thought was a direct result of studying in the teaching studio at EMS Bilthoven, attempting to create sound ‘from scratch’ there with the classic studio equipment of the time (mid ‘60s) but finding that my sounds lacked what I have come to call ‘life’. Analysing why I concluded that they lacked the flux and quicksilver spectral changes which I was used to hearing in the real-time environment, and which keep me listening. I started looking for a sound source which would be unfamiliar to listeners – thus drawing them into listening closely, given our instinctive reliance on this for security. My hope was that this close listening would reveal these inherent intricacies.

Thinking through resonant materials, most of which we’ve long used in instruments, glass came quickly to mind. I was aware of the glass harmonica of course - there was one at the Royal College of Music (London) where I studied, which was never played. Thinking beyond that, glass seemed like the promising match of rich but unfamiliar sound. Pilkington Bros was the main glass manufacturer in the UK then, and they were wonderfully generous, inviting me to their factories to explore the manufacturing processes, forms of glass and even waste products which they produce. I discovered an amazing variety of material, from cullet (glass ‘rocks’ formed as waste products in the cooling process) to ultra-thin micro glass from which electron microscopy slides are made. When I needed to travel with the production to Scandinavia, Australia, New Zealand and the US, Pilkingtons not only told me how to ship the glass safely but built me beautifully designed wooden cases - and that was a lot of glass! We traveled by ship and the glass came through perfectly. I am profoundly grateful for their warm support. Without the company I could not have created Glass Concert and my work would not have taken the swerve which has fueled me ever since.

AC: You mentioned how MEV and the Baschets were the only other sound artists using glass. You also named several other artists you’d crossed paths with at the time. Were there any among friends and acquaintances whom you felt were on a particularly similar wavelength to yourself, with the same aesthetics or sensibilities? Do you think you have a persistent aesthetic?

Annea Lockwood: It wasn’t so much my use of glass as my lifelong fascination with timbre and with exploration which characterized my composing at that time and I was drawn to artists whose ideas and work expanded my thinking and practice, pushed me beyond my habits – and still am, as with composer and trumpet virtuoso Nate Wooley. The English composer and scholar, Hugh Davies and I felt very similarly, I think, and we were close friends. His SHOZYGS are astonishing, both as instruments and as sculptures, and explore sound from the most ordinary objects, e.g. egg slicers, which is, post Duchamp, a mid-century aesthetic of course but Hugh’s work in that area is particularly fascinating.

I met Morton Feldman in the early ‘70s, as I recall, and played some of his piano pieces with him in a couple of small concerts in the UK. That was an important learning, especially in terms of duration. Letting a resonance play out entirely before striking the next tone was a central teaching and it reinforced something the glass concert had taught me too – to give a sound time - let it ‘live out its life’ fully, listening closely to the whole energy/timbre change.

This is still something which delights me, whatever the source of the sound. Yes, I do have a “persistent aesthetic” of which these two concerns are basic elements, as is my concern with sound as a conduit of connection with the non-human environment.

Another thread running through my work from the early 70s on is an interest in loosening control, enabling exploration. I think of it as initiating or enabling a sound event to start up and then standing back and seeing what happens. This started with the Glass Concerts I think, and underlies the prepared piano piece from 1996, Ear-Walking Woman; the co-composed piece Nate Wooley and I created for solo trumpet in 2017, Becoming Air; and my field recording work, in which there is always the fascination of not knowing what sounds may appear next.

AC: In the booklet for ‘Early Works’, there’s a brief mention of a program you produced for BBC radio in 1970, which ultimately led to your piece ’Tiger Balm’. I wonder if you could elaborate regarding the radio project itself, the experience of exploring the BBC archives, how one thing led to another? Do your projects often “dovetail” into each other this way?

Annea Lockwood: From 1969 – 70 I created a series of ten short programmes for BBC Radio 3 which were produced by the highly regarded producer, Madeau Stewart, and titled ‘See-Through Music’. These were broadcast during the intermissions of broadcast classical music concerts. For these I was given free rein to go through the BBC’s remarkable archives of recordings made by travelers, musicologists and others over many years, throughout the world. I was focused on the music of rituals, rituals such as: a Paiman séance from Guyana, a Main Petéri healing ceremony from Myanmar, Spring Ritual Dancing from Santander, Spain, a Tamil fire-walking procession and much more. For each programme I wrote (and spoke) an introduction, and wove the individual recordings together to create a sense of flow, often using the glass sounds I was discovering as transitions.

Of course I relished the juxtaposition of Schumann and a Korean shaman performing an exorcism, as these concerts move into Intermission and a decidedly altered space, but there was a much more serious underlying intention: I was researching music created in rituals in which trance is induced, looking for elements (the most obvious of which is repetition) which might contribute to that altered state.

Since the mid-sixties I had been thinking about music and the human body, which was one of the interests which drew Pauline Oliveros and me together, and trance was an obvious manifestation of the power of sound to affect body and mind states.

So I was digging into that, and through that channel I wanted to break out of the inculcated assumptions I carried from my training about musical materials and the range of how music is perceived, conceptualized and experienced, and by whom. It was an extraordinarily rich opportunity. I was learning different ways of thinking about music and shaping it, music and community, which reshaped my composing from then on. In the midst of these explorations I made Tiger Balm, which originally incorporated live sounds suggested by what I was hearing in those recordings, everyday sounds such as bare feet running on a wooden floor, blowing through grass blades etc. along with the tape. It was a form of theatre piece, but the tape itself proved stronger and survives on its own.

In ’70 I also created a longer programme titled Dweller in the Earth Hollow: a programme of the music, verse and lore of desert peoples, which interwove music, environmental sounds and poetry from desert communities. I was curious about whether altitude might affect musical languages and their elements; I came to no conclusion but the search was, again, really enriching.

You ask if “my projects often dovetail into one another”. Yes, always. I think I regard everything I delve into, everything I read and much of what I experience as material, and have ever since my early twenties.

AC: I’ve liked hearing you talk about ‘Tiger Balm’ in various interviews. I would say my own first impression of this one was rather Schumann/shaman-esque! Because what struck me was the pairing of seemingly disparate elements throughout the piece: the tiger vs the airplane vs the jaw harp, etc… yet whenever you talk about ‘Tiger Balm’, it’s in fact the commonality of these sounds you emphasise and want to call attention to. So that’s changed how I hear it.

You assembled ‘Tiger Balm’ over two years, did you know what sounds you wanted from the beginning? Where did you acquire the sounds: are they archival recordings or field recordings or what?

Annea Lockwood: I structured Tiger Balm something like a dream sequence, with the sounds morphing into one another through spectral resemblances or connections.

The tigers are an archival recording of tigers mating, from the BBC archives. The heart beat was from a little 45 rpm medical disc I acquired of heart rhythms. Everything else I recorded myself.

You ask if I knew what sounds I wanted to use from the beginning. Building the vocabulary of a piece is usually a mix of having an initial cluster of some related sounds in mind, and selecting one as the starting sound, then asking myself what it needs next or what quality of sound would best come next. With Tiger Balm I did something I've never done since, but which worked well, to listen to the sounds I planned to work with, internally, before going to sleep, and setting myself to dream about a possible flow or sequence.

The other guiding principle was that of osmosis, linking the flow of sounds via shared timbral/spectral characteristics, which is most obvious when the tigers' sounds lead into the rough, breathy plane, for example.

AC: You mentioned earlier “following up on the most extreme ideas”, which jumped out at me, as you come across as such an easygoing, level-headed sort of person! But then I thought about your ‘Piano Transplants’, that’s really a pretty extreme - certainly bold - idea…

I hadn’t known there were scores for this, with directions e.g. “find a shallow lake in an isolated place…”, would you develop these beforehand and try to follow through? What memorable places did it lead you?

Annea Lockwood: The scores for Piano Burning, Piano Garden and Piano Drowning all followed the event, so to speak. I can't be sure by now whether I first created those three, then decided to make the scores, or quite what the timing was, but I included them all in the first issue of Womens Work ('74). The final one - first titled 'Southern Exposure' was created years later in '82 when I was invited to contribute a score to an Italian show in Rimini titled Sonorita Prospettiche: Suono/Ambiente/Immagine. The invitation suggested scores which were truly imaginary, could not be realised and I'd had an image in mind for some time of a concert grand on a beach, anchored there but being disassembled by the sea, as a Transplant I'd love to do, but with no hope of being given even an irreparable concert grand with which to do it.

The original score I submitted was titled:

Piano Transplant - Pacific Ocean Number 5 (1972) (I was counting the permanently prepared piano as number 1.)

It reads:

Materials: a concert-grand piano, a heavy ship's anchor and chain.

Bolt the chain to the piano's back leg with strong bolts. Set the piano in the surf at the low tide line at Sunset Beach near Santa Cruz, California. Chain the anchor to the piano leg. Open the piano lid.

Leave the piano there until it vanishes.

I looked at a map of California and chose that beach because it is near the Henry Cowell Redwoods, assuming that this protected forest honored 'our' Henry Cowell. Years later when I was living in the States I went to those woods and discovered that in fact the name honors a local industrialist, and broke up!

In 2005 it was realised for the first time, near Perth, Australia by Tos Mahoney and Ross Bolleter for the Totally Huge New Music Festival in Perth. Ross, (who rescues abandoned pianos and creates the most beautiful compositions with them), found a little grand, Tos moved it to Bathers' Beach near Fremantle and we set it up there, minus the anchor. Ross and I and everyone present, plus swarms of kids, figured out how to play it, and then overnight a group of hitch hikers carted it off to their hostel! Tos put out an APB, asking for its return. The hostel manager, a bit appalled, got in touch and we took it back to the beach where a storm redistributed the legs and the lid and yet, half-filled with sand, its strings still resonated when touched. My favourite piano story.

AC: “Leave the piano there until it vanishes”.. reminds me, what was the site in London where you found discarded pianos?

Annea Lockwood: As I recall the site in London was in Wandsworth.

AC: …did you always take them away from your installations or are there still some possibly out there?

Annea Lockwood: The remnants of the pianos, usually not much more than the metal frame, are always hauled away.

AC: Fortunately we have the photos, the scores and the stories!

Well Annea it’s been a great privilege to talk to you. Do you have any further comments for our readers?

Annea Lockwood: I'd like to express my abiding gratitude to those in the UK and in the States whose encouragement, collaboration and practical help in those early years gave me the confidence to keep exploring, to take risks and shape my life as a musician. Out of that comes much joy.

AC: Hear hear!

Annea Lockwood: I also want to say how much I've enjoyed going back into those years, stimulated by such insightful questions, Andrew. Thank you for inviting me into this conversation.

AC: I’ve certainly enjoyed listening. Thanks Annea!

Annea can be found at her website https://www.annealockwood.com/. 'Glass World of Annea Lockwood' will be reissued this year on Room40 as a CD and online, with an accompanying booklet by Lawrence English.

Images

1) Original LP cover art of "THE GLASS WORLD" issued on Tangent Records, England, 1970.

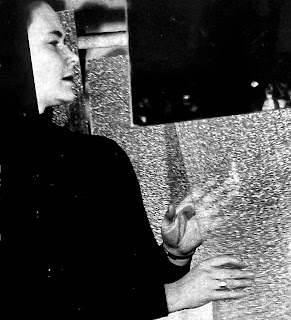

2) Annea performs the large mobile at The Glass Concert. Photo by John Goldblatt (1967, London).

3) Bottle tree, from The Glass Concert. Photo by John Goldblatt in 1967.

4) The Glass Concert, performed in London, 1967. Photo by John Goldblatt.

5) Early Works collection inserts (photo by AC).

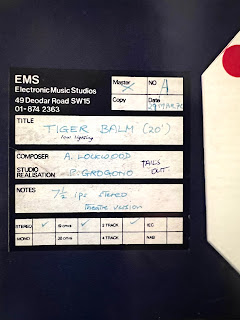

6) "Tiger Balm" master tape, 1972.

7) Piano Garden at Inglestone, Essex, England in 1970-1971. The upright piano dug a sloping trench, evoking images of a ship sinking.

8) Piano Burning at the Chelsea Embankment, London, 1968.

9) Southern Exposure at Perth, Australia in 2005.

10) Contemporary photo by Julia Dratel.